RIEK MACHAR’S POWER HARVEST IN GREATER BOR

The evolution from Community of Concern to Community of Indifference

By Maker Lual Kuol, Bor

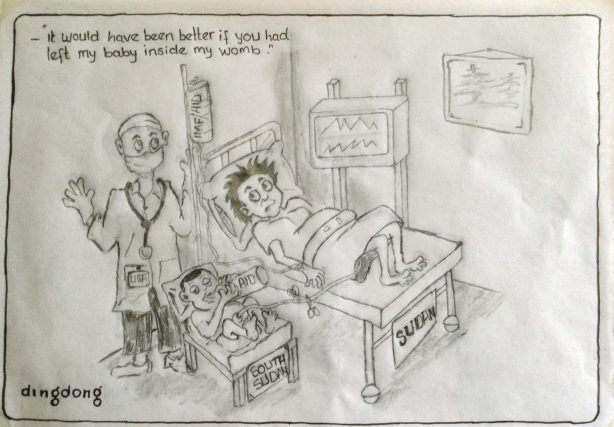

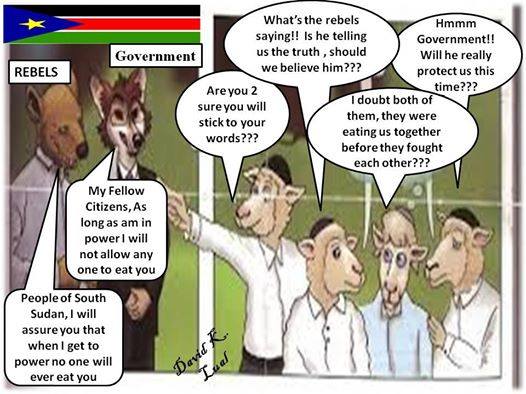

In adopting Niccolo Machiavelli principle of the end justifies the means, Riek Machar, twice carried out with impunity the genocidal massacre of the innocent people of Greater Bor. Instead of facing justice for the killings and atrocities he inflicted on the people of Greater Bor, he is being rewarded and groomed for high positions in the expected Transitional Government of National Unity (TGNU).

The legally elected Government of the Republic of South Sudan is being intimidated, pressurized and threatened to face military and economic sanctions if Riek Machar is not reinstated with all honors and medals. Death of hundreds of thousands and plight of millions of South Sudanese people is not of much concern to him (Riek) neither to some unscrupulous members of the International Community. And why not, if he is the dear child of the Troika!

As the imposed solution is at the door steps of our nation, what will be the fate of the ever soft targets of Riak Machar of Greater Bor?

- If the imposed solution of the Transitional Government of National Unity is implemented with a governor of Riek Choice?

- If the trusteeship or protract rate is imposed with the Greater Bor engulfed by their adversaries and killers; the Nuers?

- What is the guarantee that the Nuers will not repeat the massacre of the people of Greater Bor under any circumstances?

Currently, three categories of affiliates exist among the people of Greater Bor;

- Those openly supporting Riek.

- Those lying low ready to abandon the boat if seen sunk by the Troika and associates.

- And the majority who are with the government which they elected.

We appeal to our legitimate government under the leadership of our President Salva Kiir Mayardit to critically determine the fate of the people of Greater Bor before the implementation of the expected solution, such that they do not fall a victim in the hands of Riek Machar and his associate for the third time.

Sometimes back, a proposal of granting a separate administration for Greater Bor was being discussed in political corridors but it suddenly died out. The question is who is to spearhead the quest for that special status; the Jieng, Community, the Greater Bor Representatives to various houses of assemblies or the Community leaderships on both the greater or individual Counties levels?

Then worst of all is that people of Greater Bor are scattered over all South Sudan, neighboring countries and in Diaspora. How do we bring them back home? Greater Bor currently has 13 geographical constituencies to both the National and State Legislative Assemblies. Are we sure we will still maintain them intact in the coming elections?

The binding is composed of the following contents:

- Prologue

- Narrative about the massacre of 15th December 2013 – 18th January 2014

- Names of the victims of the massacre

- Some snapshots of the victims

Maker Lual Kuol

THE SUCCESSIVE GENOCIDAL MASSACRES OF RIEK MACHAR ON THE PEOPLE OF GREATER BOR

Introduction

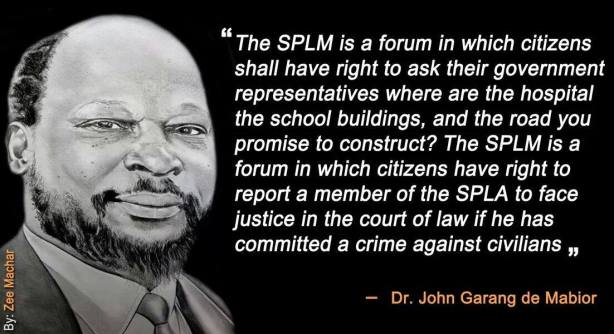

Two successive genocidal massacres have been committed by Riek Machar on the people of Greater Bor within a period of two decades. In 1991 when he split from SPLM/A, he ordered his kinsmen from the White Army composed of Lou Nuer to invade Greater Bor with the political intention of tearing the heart of John Garang, the leader of the movement by the time. In that invasion, over 20,000 people were massacred, thousands abducted, the whole wealth of the area composed of livestock was driven away leaving the destitute population without option except to seek refuge and displacement to the neighboring countries and other parts of Sudan. The rest who remained at home starved to death as there was no way to deliver any humanitarian assistance to them (Run ca poth in Dinka.) translated as the year when death was escaped and literarily by few.

With the implementation of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) and the consequent independence of South Sudan, People of Greater Bor forgot and forgave the perpetrator Riek Machar and his kinsmen and allies. A good display of that reconciliatory spirit was the apology he made in Bor in 2011 in front of a big gathering of political and community leaders and as a sign and a gesture of that good will he hugged himself with the Jonglei State Governor by the time, Kuol Manyang Juuk. Again in Juba, he apologized to Greater Bor Community at the house of Nyandeng Chol, widow of late Dr. John Garang de Mabior and one of Riek current closest allies.

Unfortunately all those apologies from Riek Machar were crocodile tears. On the 15th of December 2013, the same day shooting took place in Juba Town, Riek tentacles of Conspiracy started to engulf Bor Citizens in Bor Town and gradually the conspiracy flared into an all out genocide on the people of Greater Bor.

Who are the perpetrators of the Second Genocidal Massacre on the people of Greater Bor

Before sailing into the details of the second Riek’s massacre, Greater Bor Community would like to point hand in accusation of the following perpetrators for the role they played in the intentional and unprovoked death, maiming, rap, displacement, abduction and destruction of property.

- Riek Machar Teny Thuorgon, Former Vice President of the Republic of South Sudan.

Riek arrived Bor at around 4 pm on the 18th December in three motor boats after sneaking out of Juba following the shoot out on the 15th December. Immediately on his arrival, an attack took place all over Bor Town. This means, the forces allied to him were waiting for the arrival of their leader Riek from Juba. Militarily, most attacks are launched at dawn as a cover up for the advancing forces. Attack was not launched in the morning hours as Riek’s allied forces wanted to secure the safe arrival of their leader. When he arrived, Riek straight went to the auxiliary police force base camp behind the UNMISS Compound to direct the operations. Later at 10 pm, Riek entered the UNMISS Base Camp with Angline Teny, one of his several wives in the company of some of his close associates. Riek and some of his associates were airlifted out of the UNMISS Compound after three days by a UN chopper. On the 31st December, Riek militias of the white army stormed Bor Town and the massacre intensified.

- Hussein Mar Nyot, former Deputy Governor of Jonglei State.

Hussein Mar Nyuot, was the Jonglei State deputy governor for 8 years before appointment of the current Jonglei State Governor, John Koang Nyuon. Hussein expected himself to replace his former governor Kuol Manyang Juuk who got appointed as national minister of defense in the July 23rd 2013 reshuffle. Missing the position made him to shift allegiance to Riek. Some days before the fight in Juba, Hussein shifted the state administration to his house. Throughout the period to the attack, Hussein kept meeting Peter Gadet separately at the watch of the other cabinet ministers within his residential compound. He also continued to give instructions to the finance minister in order to release funds and fuel to the army on request of Gadet. The army is supposed to access its finances directly from the army headquarters at Bilpam in Juba not from the state.

- Gen. Peter Gadet, former SPLA Division 8 Commander

Peter Gadet, famously known for his desertions or shifting sides, was transferred to the SPLA headquarters but intelligently made his way back to Division 8 in Bor. Upon returning to Bor, he started to strategize for his attacks and massacres. He surveyed all the routes leading in and out of Bor County on the 17th of December. He killed his deputy Major General Ajak Yen in cold blood on the 17th of December. When the SPLA and the other government forces were dislodged, Gadet took charge of Bor Airport. He was the one who used to approve permits for those fleeing out of Bor Town to Juba by air. In general, Gadet was the operational commander of Riek Machar in Jonglei. All the killings and destruction were ordered and executed under his direct command.

- Gabriel Duop Lam, former Jonglei State Minister for Law Enforcement.

Duop who is supposed to protect the citizens, turned against them and butchered them. Upon Riek arrival in Bor, Duop signaled the beginning of the fight by ordering the shooting of the Police Captain Chau Mayol. Duop Lam is appointed Military Governor in waiting for Jonglei State by Riek Machar.

- The UNMISS unit in Bor Town

Riek Machar arrived Bor at 4 pm 18th December 2013 and the shooting and massacre started. At 10 pm, he was driven to the UNMISS compound with a mounted vehicle provided definitely by his lieutenants in Bor. At the UNMISS gate, the convoy was prevented by the security guards to enter but a senior UNMISS personnel intervened instructing the guards to allow the convoy to enter but the guard stood his ground though later he gave in to instructions from his superior officer. According to reports, Riek was in the company of eight others of his supporters. The guard collected all the pistols; 24 in number and removed all the magazines and dumped the pistols into the mounted vehicle which was left parked at the main gate. On the morning of 19th, Riek convened a meeting which was attended by Hussein Mar, John Koang, the newly appointed Governor for Jonglei State, Gabriel Duop Lam, the Jonglei Law Enforcement Minister, Stephen Par, Jonglei Minister of Education, Gabriel Gai Riem, Jonglei Minister of Cabinet Affairs, Beshir Deng, the Director General for the Ministry of Local Government, Moses Gatkuoth Lony, a member in the Jonglei State Assembly and others the reliable witness could not identify. Taban Deng Gai is reported to have been in the company of Riek but the witness did not know him before. Governor Koang and Gabriel Gai flew out of Bor to Juba, an indication that they refused to follow Riek Machar. After the meeting, Riek went out of the camp in Hussein Mar vehicle accompanied by other two vehicles. The number plates were wrapped up with pieces of cloth to conceal the numbers from the may be inquisitive onlookers. Outside the compound, other military vehicles were waiting for him to escort him to Malual Chat and other military posts around Bor Town. This episode of moving out of the UNMISS Compound continued for 3 days. Duop Lam, who was later appointed military Governor for Jonglei State by Riek, used to sleep inside the UNMISS Camp but early left every morning to Bor Town to participate in directing the operations under the command of Peter Gadet.

On the 21st December 2013, the basketball pitch were removed by the UNMISS soldiers and the UNMISS helicopter landed and picked Riek with a lady dressed in (Thob garment). The helicopter carrying Riek took off from the compound and headed towards the east, possibly to Gadiang or Waat, Riek strong holds. At the same time, another helicopter took off from Bor Airstrip and moved towards the north but after a short while, it reversed and straight headed for Juba. May be the movement of the two helicopters simultaneously was meant to distract the attention of people from the conspiracy of the UNMISS against the Government of South Sudan.

On the 22nd December 2013 after the departure of Riek, a drama happened when the compound was overcrowded and the facilities became scarce for the thousands of those who flocked into the compound especially the toilets and water points, the UNMISS force began to screen the displaced from the UN and NGOs personnel through ID cards. The displaced were being pushed and pulled to the other section of the camp. Hussein Mar unknown to the UNMISS soldiers was forcefully pulled out and while being dragged away, he cried out that he was the deputy Governor of Jonglei State and that he deserved a dignified treatment. In order to cool his nerves, an officer from UNMISS Contingent intervened and allowed him to sit under the tree. Hussein denied his leader Riek in few seconds like when the disciple Peter denied Jesus immediately after Jesus arrest.

On the 23rd December, when the SPLA were advancing towards Bor Town from Juba, Hussein boarded his car and tried to go out of the compound but was refused exit by the UNMISS soldiers. He then craned out his neck from the car and threatened the peacekeepers that if they did not allow him to go out, he would order the rebels to enter and kill anybody in the compound. Fearing for their lives, the peacekeepers moved their tank slightly out of the way and allowed Hussein to peacefully pass and possibly to be airlifted to Nairobi. This is how UNMISS maliciously, openly and dubiously participated in the genocidal massacre of the people of Greater Bor.

The worst is that UNMISS is sheltering the killers from Nuer as well as storing their weapons in its containers. Not that but forcefully grabbing and annexing traditional cattle camps to their base camp to shelter the killers of the owners of the land. The sheltered celebrate whenever the rebels attack SPLA positions anywhere in South Sudan. They are waiting to join Riek when he return victorious and continue the massacring of those they can lay hand on.

One of the reasons the hundreds of thousands of displaced are not returning home is the presence of the over 5,000 sheltered combatants Nuers in UNMISS Compound in Bor. Of course UNMISS is more concern with the success of Riek on the account of the innocent owners of the land (the people of Greater Bor )

From the above few facts, the genocidal massacre inflicted on the people of Greater Bor was not provoked in any way such that the UNMISS Human Rights try to be intelligent and ambiguous in its report. The genocidal massacre of 2013/2014 was more brutal than the one of 1991 which was orchestrated by the same Riek Machar using his usual super market shopping trolleys, the White Army from the Lou Nuer and Gawer.

Chronology of the Events in Bor from 15th of December 2013 to 18th January 2014

One fact should be known to all that the massacre that took place in Bor was not ever, ever provoked by anybody or situation from neither the citizens of Greater Bor nor the Government authorities as evidently proved by the following:

1- On the evening of 15th December 2013, two soldiers from the auxillary police force; namely Sgt. Mawut and Pvte. Mayor were wounded by their own colleagues. That was before the fight erupted in Juba on the night of 15th December 2013 and that was a clear evidence that there was a planned plot to overthrow the government in Juba

2- Two brothers from Twic East were killed in their house in block 4 on the night of 16th December 2013. Block 4 is adjacent to block T. which was mostly settled by citizens from Nuer Ethnic group. Block T was renamed (Ci Nuer ben) meaning Nuers have come, when they forcefully settled on it.

3- At 11 am on the 16th December 2013, Dr. Agot Alier, Bor County Commissioner, narrowly escaped an assassination attempt on his life as his vehicle was sprayed with bullets and the holes caused by two bullets can still be seen at the rear back.

4- At 4 pm 16th December 2013, two youth from Makuac Payam were shot at Makuac Junction resulting in the death of one and injury of the other.

5- On the night of 16th December 2013, Gadet deployed his forces around government installations and houses of some senior government officials possibly the ones planned to be killed when time came.

6- On the 17th December 2013, General Gadet inspected routes leading in and out of Kolnyang Payam. That inspection was a prelude to movement of the rebel and White Army forces when the fight intensified later on Bor- Juba Road.

7- At 9 pm 17th December 2013, Gadet killed his deputy Major General Ajak Yen and marched towards Bor Town in a number of mounted vehicles.

8- On the night of 17th /18th December 2013, news spread about the movement of Gadet to Bor Town and the population started fleeing the town.

9- At 4 pm 18th December 2013, Riek arrived Bor by motor boats from Juba and upon landing at the queue, shooting started and that was when Captain Chaw was shot by a colleague from Nuer Ethnic Group accompanying Gabriel Duop, the Jonglei State minister of Law Enforcement and a conspirator in the rebellion (Duop is currently appointed the military Governor for Jonglei State in waiting by Riek Mahar.

10- The poor and innocent population of Bor Town as well as the rural one aimlessly took to any direction in order to escape the death. Most people crossed to Guolyar in Awerial County, others hid in the marshes along the river and others took cover in the bushes. Those who remained in the town whether elderly, sick or insane were butchered to death. Theft, rampage raping and destruction of properties and installations were the practice during the invasion days.

11- The invaders even went to look for their victims who were hiding in bushes and marshes such as:

- Attacking those fleeing the death at motor boats’ docking stations such as the 7 people killed at Jarwong south of Bor Town..

- Crossing the gullies (Wak) and streams to seek lives of people such as what took place twice at Baidit Payam that resulted in the massacre of 29 people and driving away of over 500 heads of cattle..

- Shooting at those who sought safety across the river at Malek village where 14 people were killed including an infant.

- Attacking Kolnyang and massacring of 31 people and abduction of 11 children.

- Attacking those who took refuge in the bush at Mareng killing 25 people

- The whole town of Bor was ransacked, burnt and government and NGOs Institutions looted and destroyed.

- Mathiang, Baidit, Makol Cuei, Mareng, Wungok, Kolnyang, Thianwei, Werkok villages were burnt down.

- The usual sacred places such as churches and hospitals were not spared. Women were raped and later killed and sticks or wood inserted into their private parts.

- Thousands of people were forced to cross the river to the western bank. Others sought refuge in the marshes and high lands in the sudd area.

- In attack at Duk Payuel in Duk Payam, Riek forces from the White Army killed many people, burnt houses, cut down trees. Worst in all was the exhumation of the grave of late Paramount Chief Deng Malual who died in 1946.

The total death from this genocidal massacre reached over 2,000 people though many are still not accounted for as many are scattered over South Sudan and the neighboring countries. The massacred were buried later in four mass graves at Bor Town Cemetry.

Conclusion

It should be known to all that the massacre of Greater Bor People was:

- That what took place in Juba was a coup d’état evidently proved by the disarmament of the auxiliary police in Bor of their commanders from the Dinka ethnic group at 5 pm 15th December before the breaking out of fight in Juba on the evening of 15th December 2013.

- The successive massacres which took place in Bor were not provoked in any way by the citizens of Greater Bor.

- UNMISS evidently enhanced the massacre of the people of Greater Bor by supporting, sympathizing and facilitating Riek Machar and his associates.

Attached:

– Photos of the inhuman massacres.

– Some names of the massacred.

Compiled by:

1- Maker Lual Kuol.

ANYIDI PAYAM

BOR COUNTY

List of Civilians Killed by Riek Machar’s Rebels since 18th December, 2013

S/No. Name In Full Clan particular Age Sex Remark

1 Piok Ajak Kur Pajhok Pakom 55 m

2 Amer Garang Atem Pajhok Pakom 35 f

3 Mayen Aluong Mayen Police Pakom 64 m

4 Ajith Nook Anyang Police Pakom 68 m

5 Anyang Ajith Nook Police Pakom 18 m

6 Nyanman Jok Abuoi Police Pakom 62 f

7 Mabat Aguto Jool Apierwuong 69 m

8 Mawut Nyok Ding Apierwuong 55 m

9 Adongwei Kuol Deng Police Pakom 45 f

10 Deng Majok Kur Apierwuong 19 m

11 Ayen Kuol Kuai Apierwuong 21 f

12 Mading Jok Mayen Police Pakom 70 m

13 Dit Deng Gong Pajhok Pakom 70 m

14 Nyanthiec Awar Dit Police Pakom 62 f

15 Aman Maker Guut Police Pakom 62 f

16 Aluel Riak Keer Police Pakom 65 f

17 Leek Deng Chol Pajhok Pakom 38 m

18 Achiek Lueth Kulang Apierwuong 61 m

19 Maler Gai Kuai Police Pakom 38 m

20 Mawut Ayen Kuol Police Pakom 55 m

21 Ayen Jok Yuang Police Pakom 61 f

22 Garang Ayom Mach Pajhok Pakom 66 m

23 Appolo Pach Gar Leekrieth 76 m

24 Majok Akhau Leek Leekrieth 62 m

25 Machol Ngong Agok Leekrieth 72 m

26 Amuor Agoot Madol Leekrieth 81 f

27 Ayuen Jok Madol Leekrieth 65 m

28 Madol Kom Bior Leekrieth 58 m

29 Mayola Anyieth Akhau Leekrieth 69 m

30 Yar Anyieth Akhau Leekrieth 71 f

31 Apieu Biar Leek Leekrieth 80 m

32 Nyankor Pach Lukuac Leekrieth 60 m

33 Goop Ateny Kuereng Leekrieth 56 m

34 Nyok Bior Nyok Leekrieth 15 m

35 Piel Mayen Deng Leekrieth 62 m

36 Chol Nyok Ayook Leekrieth 76 m

37 Alier Maror Anyang Leekrieth 54 m

38 Nyuon Achien Pach Leekrieth 71 m

39 Bior Deng Yong Leekrieth 63 m

40 Amuor Deng Kuot Leekrieth 71 f

41 Ngong Chol Ajith Leekrieth 6 m

42 Yar Chol Ajith Leekrieth 4 f

43 Agok Machar Mayen Leekrieth 66 m

44 Manyok Dut Akuang Leekrieth 73 m

45 Mangar Leek Buol Leekrieth 31 m

46 Agot Leek Ateer Chuei-Magoon Chot 70 f

47 Nyanwut Achol Kon Chuei-Magoon Chot 65 m

48 Achok Nyueny Dot Chuei-Magoon Chot 45 m

49 Nyalueth Thiong Anyuat Chuei-Magoon Chot 61 m

50 Aluel Borong Anaai Chuei-Magoon Chot 72 m

51 Ajah Buol Manyang Chuei-Magoon Chot 45 m

52 Yar Awuol Deng Chuei-Magoon Chot 62 m

53 Bol Machol Mayen Chuei-Magoon Chot 35 m

54 Ayen Achiek Nhial Chuei-Magoon Chot 55 f

55 Ayuen Reng Mayom Chuei-Magoon Chot 75 m

56 Riak Reng Mayom Chuei-Magoon Chot 62 m

57 Alier Makol Bior Keer 65 m

58 Deng Angui Deng Chot 65 m

59 Makol Agou Makur Keer 80 m

60 Aleek Biar Mach Keer 71 f

61 Aliet Deng Akol Keer 62 f

62 Garang Deng Gar Keer 80 m

63 Achuerwei Deng Bior Keer 92 f

64 Keny Dekbai Riak Keer 37 m

65 Athieng Garang Alith Keer 80 f

66 Tholhok Yuang Nyieth Keer 87 m

67 Tiit Mabior Dekbai Chuei-Magoon Chot 3 f

68 Ayuen Kuol Kur Chuei-Magoon Chot 38 m

69 Ayuiu Mach Ngong Chuei-Magoon Chot 75 m

70 Akuol Kelei Ayol Chuei-Magoon Chot 68 f

71 Abiar Deng Chuei-Magoon Chot 76 m

72 Amoth Wuoi Agot Chuei-Magoon Chot 72 m

73 Erjok Machar Achuoth Chuei-Magoon Chot 37 m

74 Madol Lueth Mayen Chuei-Magoon Chot 80 m

75 Diing Deng Pakam Chuei-Magoon Chot 37 f

76 Mayen Madol Lueth Chuei-Magoon Chot 2 m

77 Nyanluak Alueng Ajuoi Chuei-Magoon Chot 61 f

78 Ayak Athiek Kur Chuei-Magoon Chot 74 f

79 Akuac Akuot Achuil Chuei-Magoon Chot 81 f

80 Mach Magon Awal Chuei-Magoon Chot 50 m

81 Achol Mach Lual Chuei-Magoon Chot 80 f

82 Awuoi Gai Nai Chuei-Magoon Chot 80 f

83 Abiei Malual Ayom Chuei-Magoon Chot 87 f

84 Ajah Yom Doot Chuei-Magoon Chot 102 f

85 Mach Gar Mach Chuei-Magoon Chot 81 m

86 Gar Kuek Gar Chuei-Magoon Chot 30 m

87 Awan Kuol Lual Chuei-Magoon Chot 41 m

88 Yar Ajok Geu Chuei-Magoon Chot 50 f

89 Nyankoor Leek Deng Chuei-Magoon Chot 50 f

90 Nyalueth Deng Bol Chuei-Magoon Chot 78 m

91 Nyabol Mach Wel Chuei-Magoon Chot 52 m

92 Ayuen Akhau Wel Chuei-Magoon Chot 37 m

93 Mamer Garang Tuung Chuei-Magoon Chot 31 m

94 Abiok Garang Deng Chuei-Magoon Chot 83 f

95 Achol Achiek Thok Chuei-Magoon Chot 5 f

96 Ngong Achiek Thok Chuei-Magoon Chot 2 m

97 Agok Kuol Deng Chuei-Magoon Chot 40 f

98 Chol Akol Bol Chuei-Magoon Chot 3 m

99 Akuek Deng Garang Chuei-Magoon Chot 80 f

100 Maluak Kang Jang Chuei-Magoon Chot 35 m

101 Jombo Apeech Ngong Chuei-Magoon Chot 77 f

102 Atong Diing Thok Chuei-Magoon Chot 3 m

103 Matuur Akech Chaboc Chuei-Magoon Chot 35 m

104 Achol Mach Chiek Chuei-Magoon Chot 66 f

105 Chol Garang Kur Chuei-Magoon Chot 31 m

106 Keth Guet Chuei-Magoon Chot 68 f

107 Akon Majok Luil Chuei-Magoon Chot 50 f

108 Angau Mach Ngong Chuei-Magoon Chot 76 m

109 Aliet Jual Anyang Chuei-Magoon Chot 61 f

110 Deng Nyok Anyieth Chuei-Magoon Chot 28 m

111 Nyabol Jok Deng Chuei-Magoon Chot 53 f

112 Mach Mayen Mayen Chuei-Magoon Chot 2 m

113 Jok Malek Deng Chuei-Magoon Chot 40 m

114 Abuui Mawut Abui Chuei-Magoon Chot 43 m

115 Abui Pur Abui Chuei-Magoon Chot 51 m

116 Gai Kelei Gai Chuei-Magoon Chot 51 m

117 Kuol Kuei Kur Chuei-Magoon Chot 67 m

118 Yar Gai Akuei Chuei-Magoon Chot 82 f

119 Deng Gaak Goch Chuei-Magoon Chot 61 m

120 Ngor Ayor Abui Chuei-Magoon Chot 28 m

121 Geu Yar Jok Chuei-Magoon Chot 30 m

122 Ayuen Achuei Gureech Chuei-Magoon Chot 28 m

123 Aguorjok Achiek Duot Chuei-Magoon Chot 90 f

124 Ding Ajith Nyok Mareng Apierweng 28 m

125 Mach Bol Ding Mareng Apierweng 60 m

126 Nyanchol Yuot Piel Mareng Apierweng 45 f

127 Akuut Pach Nai Mareng Apierweng 50 m

128 Akeer Riak Achien Mareng Apierweng 61 m

129 Aluel Leek Atuongjok Mareng Apierweng 45 m

130 Mach Lueth Mach Mareng Apierweng 50 m

131 Kuol Mathiang Deng Chuei-Magoon Chot 51 m

132 Mamer Garang Ayol Chuei-Magoon Chot 35 m

133 Mabiei Mayom Abuk Mareng Apierweng 32 m

134 Akech Makuei Ding Thianwei Boma 35 m

135 Bheer Kuol Anyieth Thianwei Boma 40 m

136 Agau Makol Ayath Thianwei Boma 32 m

137 Mach Madol Deng Thianwei Boma 40 m

138 Alier Ayuel Chengkou Thianwei Boma 70 m

139 Kelei Deng Ding Thianwei Boma 80 m

140 Kuec Tuung Lual Thianwei Boma 70 m

141 Kuei Nhial Lual Thianwei Boma 90 m

142 Achol Tong Kur Thianwei Boma 82 m

143 Akol Lukuac Bior Thianwei Boma 90 f

144 Ayong Deng Achuk Thianwei Boma 87 f

145 Yar Thiong Ayuel Thianwei Boma 81 m

146 Abuoi Jool Garang Thianwei Boma 50 m

147 Athieng Aguto Chol Thianwei Boma 106 m

148 Ajok Anyieth Achuoth Thianwei Boma 56 m

149 Abuol Garang Chol Thianwei Boma 83 f

150 Mayom Ngong Deng Thianwei Boma 79 m

151 Koor Jok Lieth Thianwei Boma 86 f

152 Athiek Anyier Akok Thianwei Boma 79 m

153 Chuti Yuol Aguto Thianwei Boma 69 m

154 Akueth Jok Ding Thianwei Boma 80 m

155 Adum Magaar Thianwei Boma 71 f

156 Ding Mangok Chol Thianwei Boma 68 f

157 Ngong Majok Ngong Thianwei Boma 50 m

158 Aluet Deng Garang Thianwei Boma 95 f

159 Maluk Mach Ding Thianwei Boma 70 m

160 Ajuong Ding Majuc Mareng Apierweng 34 m

161 Ayom Mayen Deng Mareng Apierweng 29 m

162 Ayuen Magot Bol Chuei-Magoon Chot 46 m

163 Lual Magot Bol Chuei-Magoon Chot 38 m

164 Achol Mach Achol Chuei-Magoon Chot 60 m

165 Lako Bol Mach Mareng Kucdok 38 m

166 Thon Mach Maluk Mareng Kucdok 41 m

167 Mabiel Kuei Mach Mareng Kucdok 50 m

168 Garang Mading Eguei Mareng Kucdok 30 m

169 Thon MalukMach Mareng Kucdok 30 m

170 Kuei Juac Kuonjok Mareng Kucdok 50 f

171 Guguei Majier Kuei Mareng Kucdok 26 m

172 Ayen Manyang Mach Mareng Kucdok 2 f

173 Garang Chuang Thiong Mareng Kucdok 50 m

174 Yom Ateng Dhelic Mareng Kucdok 60 f

175 Ding Lual Mareng Kucdok 90 m

176 Mach Long Mach Mareng Kucdok 90 m

177 Jambo Guec Mach Mareng Kucdok 50 f

178 Bior Arou Mareng Kucdok 88 f

179 Ateng Dhelic Mareng Kucdok 41 m

180 Makoi Wel Magot Mareng Kucdok 5 m

181 Ayen Mangar Ayuen Mareng Kucdok 40 f

182 Ayak Majok Geu Apierwuong 2 f

183 Ayoom Adiir Ayoom Chuei-Magoon Chot 82 m

184 Philip Achol Mach Achol Chuei-Magoon Chot 50 m

185 Mamer Garang Ayool Chuei-Magoon Chot 30 m

186 Mabiei Akol Deng Thianwei Boma 40 m

187 Thon Jok Nyuop Thianwei Boma 30 m

188 Mayen Amoth Nyuop Thianwei Boma 28 m

LIST OF THE PEOPLE WHO HAVE BEEN KILLEDBY THE REBEL of RIEK MACHAR

IN BAIDIT PAYAM OF BOR COUNTY

FROM/18/DECEMBER/2013 TO 18/JAN/2014

S/No Name in full Age Sex Boma

- Ajak Yen Alier 54 M Macdeng

- Panchol Garang Mabiei 52 M Machdeng

3 Maluak Panchol Lual 25 M Machdeng

4 Awuoi Anyang Bior 84 M Machdeng

5 Kuol Nyok Athieu 68 M Machdeng

6 Deng Alier Monyror 38 M Machdeng

7 Nyiel Ayuen Machar 28 F Machdeng

8 Panchol Guet Kur 67 M Machdeng

9 Adol Geu Guguei 56 F Machendg

10 Makuei Anyieth Aleer 75 M Machden

11 Aker Maloch 36 F Machdeng

12 Mabior Ajak Lueth 69 M Machdeng

13 Kuai Ajak Alier 82 M Machdeng

14 Aguto Ngong Dot 86 M Machdeng

15 Alier Garang Alier 75 M Machdeng

16 Mayendit Ayuen Mayen 45 M Machdeng

17 Mayenthi Ayuen Mayen 37 M Machdeng

18 Achol Kuai Ajak 86 M Machdeng

19 Apen Deng Yom 73 F Machdeng

20 Aman Angeth Ajak 85 F Machdeng

21 Deng Kuany Angeth 34 M Machdeng

22 Achiek Kuai Deng 37 M Machdeng

23 Alier Kuai Deng 30 M Machdeng

24 Nyanjok Yuang Agoot 78 F Machdeng

25 Nyanjur Deng Malek 52 F Machdeng

26 Akuei Kuot Kwai 48 M Machdeng

27 Yuang Aluong Changkou 20 M Machdeng

28 Ajith Jongkuch Angok 24 M Machdeng

29 Mawut Garang Arou 75 M Machdeng

30 Maker Gai Duk 64 M Machdeng

31 Bol Mayen Yuang 5o F Machdeng

32 Ayuen Aluong Chol 80 M Machdeng

33 Alier Abuong Chaw 67 M Machdeng

34 Majuot Kuol Bior 68 M Machdeng

35 Malueth Gai Deng 50 M Machdeng

36 Yom Aluong Deng 79 F Machdeng

37 Mabuol Chiew Lual 83 M Machdeng

38 Mabior Buol Duk 50 M Machdeng

39 Geu Agaau Kuany 35 M Machdeng

40 Chol Niop Chol 45 M Machdeng

41 Mabior Atheiu Achuei 78 M Machdeng

42 Tier Jok Deng 66 M Machdeng

43 Athiak Goop Bior 86 F Machdeng

44 Apar Kuol Nyuon 84 F Machdeng

45 Jur Kur Ariik 54 M Machdeng

46 Ajak Alier Malual 35 M Machdeng

47 Jok Alier Jok 36 M Machdeng

48 Ariik Ajak Luol 49 M Machdeng

49 Mabut Anyieth Anok 43 M Machdeng

50 Nyanlueth Reng Ajuong 76 F Machdeng

51 Nyankor Jarlueth Ajak 69 F Machdeng

52 Leek Jok Ajak 54 M Machdeng

53 Chuti Yar Leek 06 F Machdeng

54 Mabior Lual Anyieth 89 M Machdeng

55 Alier Diing Alaar 76 M Machdeng

56 Ajak Kur Achuoth 05 M Machdeng

57 Alier Thiong Alier 07 M Machdeng

58 Apiel Gong Bior 25 F Machdeng

59 Makuac Whel Kuot 39 M Akayice

60 Malok Kok Maguen 46 M Akuak

61 Ajak Jombo Kuol 32 M Akayice

62 Awiel Alier Malith 55 M Mathiang

63 Akuol Kon Deng 28 F Akayice

64 Adut Makuac Whel 09 F Akayice

65 Kuot Makuac Whel 07 M Akayice

67 Mac Makuac Whel 05 M Akayice

68 Achol Makuac Wel 03 F Akayice

69 Garang Dut Mathiang 70 M Machdeng

70 Yar Majok Chaath 10 F Mathiang

71 Chaath Majok Chaath 08 M Mathiang

72 Anai Nyok Anya 78 F Mathiang

73 Kudum Alith Akuei 80 F Mathiang

74 Akuany Malual Nai 60 F Machdeng

75 Anyieth Achol Jalueth 50 F Machdeng

76 Deng reng Deng 45 M Machdeng

77 Akon Jangthok Kur 47 F Machdeng

78 Kuch Alier kuch 48 M Machdeng

79 Anok Kuch Kuol 46 F Machdeng

80 Ajah Malut Barach 54 F Machdeng

81 Akur Til Makol 48 F Machdeng

82 Yar Dot Jok 49 F Machdeng

83 Apiou Anyieth Angok 81 M Machdeng

84 Gaar Malual Gaar 46 M Machdeng

85 Guut Alier Guut 20 M Machdneg

86 Adol Barach Kuc 67 M Machdeng

87 Nyalueth Thorony Agut 78 F Machdeng

88 Mawel Kuol Majok 50 M Machdeng

89 Bol Mawhel Hok 30 M Machdeng

90 Ayuen Riak Bol 43 M Machdeng

91 Hok Leek Hok 25 M Machdeng

92 Mawut Machar Ajak 44 M Machdeng

93 Kueth Reng Garang 78 M Machdeng

94 Athiak Kuch Lual 50 F Machdeng

95 Duany Akol Ajak 74 M Machdeng

96 Alier Achiek Jok 45 M Machdeng

97 Apull Atem Mabior 57 F Machdeng

98 Anai Jiel Nai 92 M Machdeng

99 Yom Mading Angok 63 F Machdeng

100 Tong Alier Tong 72 M Machdeng

101 Agot Riak Deng 70 F Machdeng

102 Adut Leek Bior 86 F Machdeng

103 Makec Alier Arou 42 M Makolcuei

104 Ateny kou Thiong 46 M Makolcuei

1o5 Panther Kuol Ayool 34 M Makolcuei

106 Anai Thuc Machar 67 F Makolcuei

107 Apat Kucha Apat 48 F Makolcuei

108 Panchol Awan Kuorwhel 53 F Makolcuei

109 Deng Majak Deng 32 M Makolcuei

11o Awuol Deng Diing 58 M Makolcuei

111 Akur Ajieu Arou 67 F Makolcuei

112 Majuang Garang Kuol 37 M Makolcuei

113 Ayuen Athieu Achuei 64 F Makolcuei

114 Dit Alou Dit 61 M Makolcuei

115 Mading Nyuon Kur 54 M Makolcuei

116 Koor Barach Deng 39 F Makolcuei

117 Ayak Luk Ngong 55 F Makolcuei

118 Kur Deng Kur 69 M Makolcuei

119 Aluel Gureech Nyuon 42 F Makolcuei

120 Amuor Juuk Kuch 35 F Makolcuei

121 Nhial Jok Nhial 40 M Makolcuei

122 Lual Nyanreeh Majok 48 M Makolcuei

123 Akech Madit Dhuol 38 M Makolcuei

124 Malual Nyok Chengkou 23 M Makolcuei

125 Jongkuc Awan Bior 78 M Makolcuei

126 Malith Abuol Barach 38 M Makolcuei

127 Adau Ajak Atem 53 F Makolcuei

128 Ayuen Kuol Mayen 12 F Makolcuei

129 Majok Nyok Panjok 81 M Makolcuei

130 Achiek Kuc Aneet 42 M Makolcuei

131 Akham Deng Akham 90 M Makolcuei

132 Lith Achiek Dot 71 F Makolcuei

133 Awhel Anyuon Anai 49 F Makolcuei

134 Mac Kur Anyangdit 66 M Makolcuei

135 Alaak Keech Buol 37 F Makolcuei

136 Malueth Riak Mading 38 M Makolcuei

137 Agook Tohol Deng 54 F Makolcuei

138 Majok Mam Maluth 70 M Makolcuei

139 Anyang Nhial Lual 58 M Makolcuei

140 Mabior Dhuka Mabior 48 M Makolcuei

141 Wal Apeech Adol 45 M Makolcuei

142 Matiop Chol Mach 34 M Makolcuei

143 Achol Joh Deng 36 F Makolcuei

144 Ajuur Chol Lueth 45 F Makolcuei

145 Adum Deng Makeer 43 F Makolcuei

146 Nyandit Magot Ariik 29 M Makolcuei

147 Nyanlueth Riak Mading 20 F Makolcuei

148 Thon Ayuen Nhial 33 M Makolcuei

149 Garang Jam Lual 67 M Makolcuei

150 Ajoh Ajok Ajak 38 F Makolcuei

151 Alith Awan Deng 48 M Makolcuei

152 Nyanlueth Deng Biar 32 F Makolcuei

153 Chuir Lueth Alier 26 F Makolcuei

154 Nyok Piel Ajak 68 M Makolcuei

155 Achol Nyok Piel 28 F Makolcuei

156 Makuei Nyok Piel 51 M Makolcuei

157 Ayom Madul Arou 30 M Makolcuei

158 Ateny Bul Angeth 48 M Makolcuei

159 Aluel Kuol Kuai 19 F Makolcuei

160 Gai Joh Akuok 37 M Tong

161 Agoot Thiel Beny 68 F Tong

162 Akuol Whel Akhau 73 F Tong

163 Lual Buol Lueth 09 M Tong

164 Mach Bior Maghot 21 M Tong

165 Awuol Makuei Manyan 45 M Tong

166 Guet Apiou Anyuon 75 F Tong

167 Yuang Aguto Alith 35 M Tong

168 Mairar Dot Alith 44 M Tong

169 Kelei Gai Nai 68 M Tong

170 Abeny Dhuol Angeer 78 F Tong

171 Ayuen Jongkuc Kuoi 38 F Tong

172 Mayar Jupuur Anyieth 63 M Tong

173 Akuol Amac Lual 73 F Tong

174 Anyieth Apiou Makur 65 F Tong

175 Manyok Machaar Akuok 35 M Tong

176 Yom Gai Mach 64 F Tong

177 Achol Mooch Mathiang 52 M Tong

178 Akech Athiak Machar 32 M Tong

179 Moch Garang Moch 35 M Tong

180 Peer Maluil 63 F Tong

181 Yom Akuei Mach 61 F Tong

182 Nyang Dhaal Akol 79 F Tong

183 Garang Parach Garang 16 M Tong

184 Manyok Akuok Anyang 70 M Tong

185 Nyankoot Jok piel 75 F Tong

186 Apiou Anyieth Yuang 49 F Tong

187 Atong Deng Akhau 56 F Tong

188 Thongboor Nyuon Bil 63 M Tong

189 Machar Dheiu Machar 54 M Tong

190 Deng Njuotnyin lual 84 M Tong

191 Panchol Mach Jok 37 M Tong

192 Deng Abuol Deng 39 M Tong

193 Mawhel Thiong Kut 66 M Tong

194 Manyok Ajiok Kut 53 M Tong

195 Amuor Deng Khom 52 F Tong

196 Kuir Makol Mawan 03 M Tong

197 Ayak Ajak Kuer 02 F Mathiang

198 Anyieth Kelei Anyinyot 35 M Mathiang

199 Bol Ayuen Thiong 40 M Mathiang

200 Akec Mayen Ajuoi 35 F Mathiang

201 Mabior Majak Kou 41 M Mathiang

202 Amoch Arou Deng 51 F Mathiang

203 Maluk Anyinyot Kuot 59 M Mathiang

204 Nhial Buol Ajuong 20 M Mathiang

205 Majok Buol Ajuong 25 M Mathiang

206 Kuei Leek Mayen 50 F Mathiang

207 Diing Nyang Aliet 67 F Mathiang

208 Awur Garang Reng 60 F Mathiang

209 Maker Goor Athou 54 M Mathiang

210 Maker Deng Mathiang 67 M Mathiang

211 Panchol Anyieth Bol 54 M Mathiang

212 Aguto Mac Ruar 61 M Mathiang

213 Atet Jok Atet 65 F Mathiang

214 Goop Maluak Kuot 02 F Mathiang

215 Mamer Mayen Nuer 35 M Mathiang

216 Madel Lueth Nuer 43 M Mathiang

217 Mading Ayuen Madol 38 M Mathiang

218 Machar Lual Kur 31 M Mathiang

219 Lual Koryom Lual 42 M Mathiang

220 Deng Majok Ajuoi 51 M Mathiang

221 Panchol Reng Ajah 68 M Mathiang

222 Areng Majak Ayuen 02 F Mathiang

223 Akon Nyuon Kelei 32 F Mathiang

224 Pandek Mamour Kuc 06 M Mathiang

225 Diing Kureng Ajiok 67 F Mathiang

226 Ajoh Nuer Mach 58 F Mathiang

227 Ayuen Agoot Akoi 53 M Mathiang

228 Awur Garang Ayiik 54 F Mathiang

229 Awiel Alier Malith 45 F Mathiang

230 Alier Chot Leek 91 M Mathiang

231 Nyok Jok Marial 92 M Tong

232 Aliet Chiengkou Anyang 76 F Tong

233 Anak Riak Abuong 63 M Tong

234 Abit Mamer Deng 80 F Tong

235 Mabior Amol Dor 57 M Tong

236 Akuach Yuom Pach 95 F Tong

237 Akur Gop Ayuen 84 F Tong

238 Akon Rech Thiong 78 F Tong

239 Ayen Kurwel Ahou 100 F Tong

240 Akut Kuol Marial 90 F Tong

241 Garang Awan Nyok 18 M Tong

242 Manguak Aguto Mayen 58 M Tong

243 Majur Kon Riak 36 M Tong

244 Gai Deng Mayen 65 M Tong

245 Ayen Riak Goor 75 F Tong

246 Achiek Mayen Alier 2mths M Tong

247 Kuol Alaak But 81 M Tong

248 Biar Ngor Deng 25 M Tong

249 Aleek Mayen Adeng 37 F Tong

250 Ajah Agoot Madol 49 F Tong

251 Jool Mayen Yuang 36 M Tong

252 Ayuen Deng Mayen 72 M Tong

253 Achol Aborich Angeth 39 F Tong

254 Maror Atong Kur 25 M Tong

255 Ayuen Makec Kur 15 M Tong

256 Ateny Alaar Awan 37 F Tong

257 Akut Kuol Marier 36 F Tong

258 Ayuen Alier Chot 57 M Tong

259 Yen Abuoi Yen 15 M Tong

260 Mangar Alier Dot 65 M Tong

261 Garang Deng Dhel 71 M Tong

262 Panchol Kuol Anyuch 41 M Tong

263 Ayom Giet Anyang 65 M Tong

264 Alier Bol Makol 27 M Tong

265 Achol Deng Akook 48 F Tong

266 Angeth Thongbor Kur 42 F Tong

267 Ayen Kucha Apar 45 F Tong

268 Whel Jil Ajak 91 M Tong

269 Ajak Muoth Ajak 38 M Tong

270 Kelei Makol Riak 81 F Tong

271 Alier Chiek Kok 25 M Mathiang

272 Makuac Maketh Agol 68 M Mathiang

273 Atit Akuei Nyang 71 M Mathiang

274 Aguek Achilim Juuk 65 M Mathiang

275 Ngor Ayuen But 38 M Mathiang

276 Chaw Mayol Juuk 48 M Mathiang

277 Achiek Malith Bol 24 M Mathiang

278 Manyuon Alier Adol 25 M Mathiang

279 Kuot Angau Juuk 26 M Mathiang

280 Ayollo Kur Ayom 45 M Mathiang

281 Joh Dot Joh 14 M Mathiang

282 Akec Majok Leek 25 M Mathiang

283 Adol Thongbor Maketh 12 F Mathiang

284 Agok Makuac Maketh 07 F Mathiang

285 Abiei Kang Ayool 73 F Mathiang

286 Awut Ayuen Majok 05 F Mathiang

287 Ajok Mayol Mabior 08 F Mathiang

288 Lual Thiak Bol 26 M Mathiang

289 Ayuen Mabior Kuac 38 M Mathiang

290 Awuok Lual Gak 30 M Mathiang

291 Anyang Ayuen Thon 60 M Mathiang

292 Mach Ajak Mayen 49 M Mathiang

293 Akuei Amool Aluel 45 M Mathiang

294 Garang Deng Majak 72 M Mathiang

295 Akuel Alith Kur 78 M Mathiang

296 Thiak Ayuen Mach 67 M Mathiang

297 Mayen Panchol Ayuen 17 M Mathiang

298 Abuoi Akuei Nyok 61 M Mathiang

299 Jok Gai Jok 42 M Mathiang

300 Agoot Alith Kuot 79 F Mathiang

301 Duom Deng Mabior 60 F Mathiang

302 Bior Thon Agoot 20 M Mathiang

303 Kawai Mamuor Gup 25 M Mathiang

304 Mamuor Gup Deng 55 M Mathiang

305 Kuol Gup Deng 45 M Mathiang

306 Deng Abuoi Nyok 45 M Mathiang

307 Ayor Magook Alier 51 M Mathiang

308 Nyuop Akuei Jok 31 M Mathiang

309 Kuot Aluel Akuei 22 M Mathiang

310 Majok Akuei Nyok 48 M Mathiang

311 Apeu Nhomrom Dau 63 F Mathiang

312 Garang Deng Majak 75 M Mathiang

313 Kuec Juuk Kur 78 M Mathiang

314 Guet kuot Akuot 70 M Mathiang

315 Deng Jok Garang 30 M Mathiang

316 Ayak Deng Ngor 81 F Mathiang

317 Biol Kuec Juuk 10 F Mathiang

318 Akuot Mabior Deng 74 F Mathiang

319 Alier Akuei Kuot 70 M Mathiang

320 Ajak Kuol Anyieth 30 M Mathiang

321 Mamer Angok Akei 53 M Mathiang

322 Diing Kur Dot 75 F Mathiang

323 Guet Leek Nhomrom 59 F Mathiang

324 Achol Gai Arou 45 F Mathiang

325 Awei Riak Agoot 70 F Mathiang

—

JALLE PAYAM

BOR COUNTY, JONGLEI STATE

Date: 24/1/2014

BELOW IS THE LIST OF WAR VICTIMS WHO WERE KILLED BY THE NUER WHITE ARMY DURING DECEMBER 18TH TO 31TH 2013 FROM ALLIAN COMMUNITY IN DETAILS OR VICTIMS OF RIAK MACHAR’S SECOND REBELLION.

S/NO NAME IN FULL SEX CHIEF Location REMARKS

- Bol Juol gupngong M AyiiMabiorMayen Malakal

- Akem Ayii Akech M “ “ “

- Deng Ayuen Nyok M “ “ “

- Achol Mayen Mareng F “ “ “

- Amuor Deng Achiek F “ “ “

- Adhieu Malou Wei F “ “ “

- Tiit Amol Gut F “ “ “

- Achuek Deng Arou M “ “ “

- Jok Magot Jok M “ “ “

- Maluak Akech Agou M “ “ “

- Matiop Ayii Awur M “ “ “

- Atong Ayii Jok F “ “ “

- Jok Ayii Jok M “ “ “

- Malek Deng Hok M “ “ “

- Jok Ayii M “ “ “

- Majok Thiak Alier M “ “ “

- Akech Magot Garang F “ “ “

- Reech Mayen Dor M “ “ “

- Deng Adut Deng M “ “ “

- Mabior Ayuen Ngong M “ “ “

- Agou Akech Agou M “ “ “

- Anyieth Kur Anyang M “ “ “

- Thiak Alier Arou M “ “ “

- Alier Arou Achak M “ “ “

- Arou Alier Achak M “ “ “

- Kuol Ayii Awur M “ “ “

- Buol Dor Buol M “ “ “

- Akech Agou Kot F “ “ “

- Abuk Mabiei Deng F “ “ “

- Lueth Deng Arou M “ “ “

- Atem Manyuon Atem M “ “ “

- Malir Manyuon Atem M “ “ “

Boma-Kuei–Payach Wut Apiu

- Akech Ayom Akuot M

- Reng Wuany Arou M

- Akuch Lueth Nhial F

- Buol Magok Matung M

- Ajok Alop Apiu F

- Manyok Jok Garang M

- Mamer Amol Deng M

- Yar Alier Deng M

- Mathung Jok Ayom M

- Amol Mading Amol M

- Apiu Amol Deng F

- Matiop Kuol Kuar M

- Apat Malual Manyiel M

- Apiu Malual Manyiel F

- Manyang Malual Rok M

- Nhial Akuot Ayom M

- Madit Apiu Jok M

- Arou Garang Ngok M

- Garang Ngok Arou F

- Kuany Yuang Kuany M

- Yar Ajoh Kuany F

- Pat Magok Apiu M

Buol Alier Thon

- Panther Alier Anur Ayom M Bentiu

- Wel Anyar Ayen Wel M

- Chol Anyieth Dut M

- Manyok Ayom Magon M

- Ayom Magon Ayom

Chief Akuot Chol Akuot

- Atem Ngor Atem M

- Mayom Deng Magong M

- Nyanabot Akech Amuom F

- Deng Matiop Kur M

- Dut Ngor Dut M

- Kuo lNyok Lual M

- Bol Deng lual M

- MayomThungMayom M

- Kur Deng Awur M

- Dut Deng Dut M

- Deng lueth Nul M

- Deng Mayom Dut M

- Nhial Anyieth Nhial M

- Nyandeng Monyyong F

- Abuol Awur Kur F

- Kut Nhial Ajak M

- Panom Kut Akech M

- Maluk Lual Dut M

- Thuch Deng Nul M

- Manyang Dut Lual M

Chief Kuai Ayuen

- Maluak Mabior Reech M

- Jol Manyok Kuor M

- Acury Agent Ngong F

- Buol Piel Bol M

- Aruai Malei Puok F

- Boni Dal F

- KuaiAjak Awur M

- Kalali Deng Arou M

- Garang Jok Akuak M

- Majur Ayuen Bol M

- Achol Pei Deng F

Chief: Machiek Biar Deng

- Deng Kok Achol M

- Kuol Ayom Lual M

- Adit Amol Kuot F

- Ateny Kuot Kok F

- But MajuchThuch M

- Anyieth Akoi Atem M

- Kuot Akok Lual M

- Biar Lual Kuai M

- Bol Yuot Chagai M

- Thiong Agot Kuochrot M

- Ret Amuor Adut M

- Ayen Agou Gumbiir F

- Lual Makuach Alual M

- Nyanrach Nhial Anyang F

- Anyieth Dut Ajak F

- Arou Alier Deng M

- Anyieth Dhuor Yoi F

- Awan Akuek Lual M

- Buol Deng Agamjok M

- Buol Deng Kur M

- Lual Akuoch Arok M

- Anyieth Kulang Deng F

- Anyieth Deng Malith M

- Achok Deng Thuch F

- Anyang Makol Kur M

- Atong Mach Deng F

- Lual Deng Kur M

- Lual Kuai Lual M

Chief: Akuot Chol Akuot

- Ayor Abol Riak F

- Akech Akoi Malual F

- Jol Awuou Deng M

- Kuol Ngor Amuom M

- Chol Ajak Dut M

- Marial Nhial Amuom M

- Deng Amuom Deng M

- Bol Amuom Deng M

- Chol Goor Agany M

- Agany Goor Agany M

- Ayak Abiar Akol F

- Nyanchiek Jok Arou F

- Kut Chuir Kut M

- Kuch Akech Nhial M

- Aguek Nhial Lual M

- Maluk Ajak Mabiai M

- Chol Thon Achieu M

- Akech Maluk Lueth F

- Madhier Nhial Anyieth M

- Nhial Achieu Lual M

- Kuch Kur Deng M

Chief: Alier Anyuon Deng

- Deng Apui Manyiel M

- Malith Mabior Deng M

- Ajoh Akuak Dhuor F

- Akuang Deng Kur F

- Arok Apui Deng M

- Athou Magar Makuei F

- Adhieu Akuot Mayen F

- Manyok Akuot Garang M

- Apiu Mabior Deng F

- Anyuon Deng Anyuon M

- Apiu Manyiel Deng M

- Majok Akoi Anyuon M

- Yar Achiek Deng F

- Mabior Malual Akuot M

- Mabiei Malual Akuot M

- Akuot Alier Anyuon M

- Manyiel Akuot Apiu M

- Anyuon Akuot Apiu M

- Mum Abuoi Anyuon M

- Achiek Maker Anyuon M

- Agot Lueth Rop M

- Bol Ajak Mabior M

- Manyiel Apiu Manyiel M

- Marol Aput Manyiel M

- Adut Majok Aput F

- Deng Anyuon Deng M

- Deng Akuot Ayuen M

- Akuot Ayual Deng M

- Anyieth Moror Kuer F

- Anyuon Akuot Mabiei M

- Apiu Maluak Anyieth F

- Achol Amaar Maluak F

- Akech Anyuon Apiu F

- Marial Akuot Apiu M

- Ayom Deng Makuach M

- Anyuon Majok Mayen M

- Athou Nhial Jok F

- Anyang Bior Marial M

- Anyuon Deng Akuot M

- Marial Gon Akuot M

- Gutbeny Bol Ajak M

- Adut Awac Chol F

Executive Chief: Garang Ayuen

- Buol Jok Mabiei M

- Aguto Agor Atum M

- Kur Mabior Kur M

- Thiong Bior Jok M

- Ajak Akuok Bior M

- Ghai Maghar Anyieth M

- Malual Buol Awan M

- Magot Jok Deng M

- Aluel Garang Chawuoch F

- Deng BiarYol M

- Thiong Anyak Biar M

- Abuol Akuei Majuch F

- Bol Kuot Guet M

- Nyanlueth Adhuong F

- Ayen Angok F

- Awan Jool Buol F

- Apiu Thiak M

- Ngor Riak Lual M

- Dut Thiak Dut M

Prepared by Juet Community

AKUAI-DENG BUMA,

__________________________________________________________________________

S/NO Name in full Rank Ages Sex Subsection

- KuolGurechApiu Diploma 42 M Padong/Chamany

- MatiopAbuk Civilian 50 M ,,, ,,,,

- Thon Nhial Thon Civilian 129 M ,,, ,,,,

- AgotMathiang Civilian 85 F ,,, ,,,,

- MajokAnyiethNhial Civilian 55 M ,,, ,,,,

- NyokCholAjak Civilian 130 M ,,, ,,,,

- Machar Deng Kuot 2nd LT 40 M ,,, ,,,,

- MahmadHusienMadit Director 63 M ,,, ,,,,

- AchiekMaluk Mach Civilian 44 M ,,, ,,,,

- AyenAjuuJok Civilian 78 F ,,, ,,,,

- AyoolChauMuojok Civilian 75 F ,,, ,,,,

- Awar Deng Akundur Civilian 46 F Pabeer

- MalualMabiorDit ” 68 M ,,, ,,,,

- NgorMalual Kun ” 47 M ,,, ,,,,

- GaiDitMabior ” 73 M ,,, ,,,,

- Deng NyokKuir ” 54 M ,,, ,,,,

- AthiengAliyou ” 50 F ,,, ,,,,

- AkorRiakKut ” ‘ 60 M ,,, ,,,,

- MabiorAjakAlith ” ‘ 60 M ,,, ,,,,

- AkuolNgardit ” ” 64 F ,,, ,,,,

- AkuchYuangKuorwel Civilian 80 f ,,, ,,,,

- MakethAdutBior Civilian 88 M ,,, ,,,,

- ArouWuoiMayen Civilian 60 M Awenga

- Mum Kuch Dot Major 62 M ,,, ,,,,

- Thon MajokNyok Civilian 30 M ,,, ,,,,

- BiarAjithBiar Civilian 36 M ,,, ,,,,

- AluelChuir Anyang Civilian 70 F ,,, ,,,,

- MalonyCholJok Civilian 78 M ,,, ,,,,

- AbuolAyak Civilian 62 F ,,, ,,,,

- CholBol Deng Civilian 12 F ,,, ,,,,

- AngokMalekAwuok Civilian 75 M Pakei/Burju

- Anyieth Deng Kur Civilian 45 M ,,, ,,,,

- AbuoiLuethBior Civilian 62 M ,,, ,,,,

- BiorAjohBior Civilian 28 M ,,, ,,,,

- AngokKuolAngok BA of Degree 28 M ,,, ,,,,

- AchiekKeechNyok Civilian 63 M ,,, ,,,,

- NyankorAngok Civilian 78 F ,,, ,,,,

- Kur Deng Kur Civilian 55 M ,,, ,,,,

- KuolGurechBiar LT .COL. 47 M Bor Town

- NyawurAbuoiNhial Civilian 47 F Malual-Agorbaar

KOLMEREK BOMA

S/N Name in full Sex Place of KIA Age Clan

- Malek Angeth Angok M Bor Town 45 Kol..

- Deng Anyieth Arou M Bor Town 53 Kol..

- Mangar Deng Angok M Bor Town 35 Kol..

- Bheer Ajuu Jok M Bor Town 53 Kol..

- Maluk Ayuen Mayen M Bor Town 60 Kol..

- Athung Jok Achiek F Bor Town 46 Kol..

- Angeth Mabior Deng M Bor Town 38 Kol..

- Jok Geu Nyingut M Bor Town 55 Kol..

- Akeer Mabiei Ngang F Bor Town 70 Kol..

- Malith Angok Malith M Bor Town 65 Kol..

- Ayuen Khor Nyiel M Bor Town 38 Kol..

- JemaYar Jok M Bor Town 25 Kol..

- Achiek Monyychok Thon M Bor Town 40 Kol..

- Chol Malok Jongthok M Bor Town 28 Kol..

- Yar Anyieth Arou F Bor Town 60 Kol..

- Nyanchiek Awan Gaar F Bor Town 50 Kol..

- Nhial Ajok Deng M Bor Town 05 Kol..

- Kuol Thon Jongthok M Bor Town 68 Kol..

- Panchol Garang Majok M Bor Town 58 Kol..

- Akuol Anyieth Nhial F Bor Town 67 Kol..

- Chol Kuur Jok M Bor Town 67 Kol..

- Thokluoi Kuany Ayol M Bor Town 70 Kol..

- Abiar Ayuel Ajak F Bor Town 68 Kol..

- Yom Reng Angeth F Bor Town 56 Kol..

- Yar Juuk Mach F Bor Town 39 Kol..

AYOM GAL

S/N NAME IN FULL SEX

- Jol Alier Dit M

- Majok Bol Ayom M

- Riak Bol Ayom M

- Reech Akuak Mayen -Sub-Chief M

- Athiek Ajhook Mathiang Sub-Chief M

- Anyieth Aguto Nhial M

- Anyieth Aman Anyang M

- Leek Wal Reech M

- Nyatiop Leek Wal F

- Achok Khok F

- Awel Janthok F

- Majak Mayen M

- Akur Diyo Gong F

- Adau Lueth F

- Reech Nyatiop Leek M

- Min Nyatiop Leek F

- Nhial Ajhok Nhial M

- Ateny Deng Kuot M

- Nhial Nyok Nhial M

- Jok Deng Kuol M

- Ghai Jokuch Thiong M

- Makol Guong Makol M

- Garang Deng Ayiei M

WUT-YACH

S/NO NAME IN FULL SEX

1 Michael Reng Mum M

2 Tiel Luk Athoch M

3 Ayuen Nhial Ajok M

4 Mayom Kuer Jok M

5 Ayom Kuer Ayom M

6 Malual Awur Garang M

7 Amour Thok-Jang F

8 Kelei Rok Reech M

9 Amer Anyijong M

10 Malith Athoch Jok M

11 Angeth Diing Alaak F

12 Ajok Nhial Garang M

PAGEU SUB CLAN

13 Garang Deng Ayiel M

14 Athou Riak Magaa F

15 Ayuen Chol Deng Mayen M

16 Narech Mabior Ayom F

17 Chol Biar Deng M

18 Deng Magot Deng Ayiel M

19 Ayak Wuoi F

20 Ayuen Alith Nomrou M

21 Ngang Anyieth Ngang M

22 Kelei Chol Biar M

23 Riak Ayuen Kuot M

24 Ayen Maketh Wai F

25 Garang Deng Chol M

26 Agau Ayiel Deng M

AWAN CLAN PEOPLE KILLED BY NUER (Killed in Bor Town)

S/NO NAME IN FULL SEX

1 Malith Lueth Aweer M

2 Achol Gai Arou F

3 Mach Garang Deng M

4 Ayuen Deng Mach M

5 Buol Agook Jil M

6 Riak Malong Riak M

7 Ayen Jok Chot F

8 Garang Nyok Arou M

JONGLEI STATE

KOL-NYANG PAYAM

Summary report of people killed by Riek Machar rebel forces in

Kol-nyang Payam on 18th December, 2013 – 5th February, 2014

The list by Bomas and Chiefs.

S/N NAME OF DECEASED SEX AGE BOMA CHIEF REMARKS

1 Mabior Mayen Garang M 48 Gak Aguto Makol

2 Thon Garang Nhial M 75 Gak Aguto Makol

3 Wut Aguto M 60 Gak Aguto Makol

4 Marial Ayol Goor M 47 Gak Aguto Makol

5 Achol Jool Alier F 79 Gak Aguto Makol

6 Guet Gai Ayuel F 80 Gak Aguto Makol

7 Joh Kur-bach Deng M 45 Gak Mabior Ater

8 Bol Lual Gong M 35 Gak Aguto Makol

9 Aguto Deng Chol M 60 Gak Aguto Makol

10 Deng Magok Deng M 70 Gak Mabior Ater

11 Areu Magot Areu M 55 Gak Nai Wal

12 Alier Nyuon Chol M 78 Gak Nai Wal

13 Ajok Jok Kur M 58 Gak Aguto Makal

14 Ayor Makol Bior F F Gak Nai Wal

15 Kur Ajuong Kur M 50 Gak Nai Wal

16 Ajith Jok Madit F 60 Gak Nai Wal

17 Amer Mading Madol F 30 Gak Maper Alier

18 Gai Abol Nhial M 40 Gak Maper Alier

19 Akoi Guarak Mach M 45 Gak Maper Alier

20 Garang Wel Garang M 96 Gak Aguto Makol

21 Panchol Deng Nhial M 60 Gak Maper Alier

22 Yom Achiek Yom M 40 Gak Maper Alier

23 Garang Chol Deng M 36 Gak Aguto Makol

24 Majok Jol Ngong M 40 Gak Garang Gai

25 Machar Dhaal Anyieth M 25 Gak Chol Alier

26 Kuol Mathiang Deng M 60 Gak Garang Gai

27 Tier Dut Jok M 70 Gak Chol Alier

28 Ariik Kuai Ariik M 17 Gak Chol Alier

29 Anai Joh Maluil M 90 Gak Maper Alier

30 Deng Alier Deng M 25 Gak Maper Alier

31 Garang Maluk Anyieth M 18 Gak Aguto Makol

32 Ajok Jok Chol F 70 Gak Chol Alier

33 Nyantet Jong-gook F 80 Gak Aguto Makol

34 Gai Kelei Gai M 55 Gak Aguto Makol

35 Ayom Mayen Deng Nyuat M 20 Gak Garang Gai

36 Juma Agot Ajak M 35 Gak Garang Gai

37 Atong Puka Mabit F 7 Gak Garang Gai

38 Garang Alier Garang M 37 Gak Aguto Makol

39 Akol Achol Akol M 30 Gak Mach Akol

40 Makoth Guem Adut M 75 Pariak Waat Nyieth

41 Achok Ajak Bior F 65 Pariak Alier Them

42 Mangok Guem Adut M 65 Pariak Waat Nyieth

43 Yom Ajak Aret M 40 Pariak Waat Nyieth

44 Small child of Yom M 01 Pariak Waat Nyieth

45 Lado-dit Akon M 60 Pariak Waat Nyieth

46 Lou Alier Machot M 30 Pariak Waat Nyieth

47 Aru Panchol Thiek M 30 Pariak Waat Nyieth

48 Diing Deng Aboch F 70 Pariak Waat Nyieth

49 Mayol Deng Majuch M 45 Pariak Waat Nyieth

50 Awan Wel Reech M 40 Pariak Alier Them

51 Nyankot Abolich Nhial F 50 Pariak Waat Nyieth

52 Ayong Adut Jok M 30 Pariak Waat Nyieth

53 Mawut Akech Chuer-wei M 38 Pariak Waat Nyieth

54 Nyirou Majuch Achok Nyirou M 85 Pariak Waat Nyieth

55 Mayol Yuot Tong M 48 Pariak Manguak Thuma

56 Mach Kam Mach M 28 Pariak Manguak Thuma

57 Madding Riak Deng M 85 Pariak Pandek Mach

58 Yar Wel Reech F 35 Pariak Alier Them

59 Nyidieng Chek/Leper F 44 Pariak Waat Nyieth

60 Garang Aluong Nyang M 33 Pariak Waat Nyieth

61 Garang Lueth Anyieth M 38 Chuei-keer Pandek Mach

62 Mading Mayom Garang M 44 Chuei-keer Pandek Mach

63 Panchol Deng Jok M 52 Chuei-keer Pandek Mach

64 Bathou Agau Bathou M 58 Chuei-keer Mach Kucha

65 Deng Goti Deu-tong M 56 Chuei-keer Pandek Mach

66 Yom Achiek Jok F 48 Chuei-keer Pandek Mach

67 Alei Akol Garang F 60 Chuei-keer Pandek Mach

68 Thieu Achiek Jok F 64 Chuei-keer Pandek Mach

69 Achol Ajal Kur F 73 Chuei-keer Mach Kucha

70 Akur Aguer-jiei Nai F 71 Chuei-keer Pandek Mach

71 Ater Yuot Awar-dit F 71 Chuei-keer Mach Kucha

72 Magot Mach Kuor-wel M 60 Chuei-keer Mach Kucha

73 Marial Akol Ajok M 55 Chuei-keer Marial Maluil

74 Mading Nyok Garang M 55 Chuei-keer Marial Maluil

75 Reech Riem M 65 Chuei-keer Marial Maluil

76 Garang Dhieu Garang M 45 Chuei-keer Marial Maluil

77 Aluel Ajak Ayol F 79 Chuei-keer Marial Maluil

78 Aluel Bol Deng F 79 Chuei-keer Marial Maluil

79 Athor-bei Anyar Nyok M 70 Chuei-keer Aguto Chol

80 Mach Achuek Mach M 42 Chuei-keer Aguto Chol

81 Kur Kelei Ajuong M 33 Chuei-keer Aguto Chol

82 Thong-bor Kur Akau M 33 Chuei-keer Aguto Chol

83 Deng Mading Deng M Chuei-keer Garang Athiek

84 Riak Garang Ngong M 76 Chuei-keer Manyang Keny

85 Panchol Akol Aguto M 28 Chuei-keer Manyang Keny

86 Akuei Jok Magok M 58 Chuei-keer Manyang Keny

87 Panchol Kuol Ngueny M 28 Chuei-keer Manyang Keny

88 Achol Mathon Pach F 58 Chuei-keer Manyang Keny

89 Akech Mawut Jok M 30 Chuei-keer Manyang Keny

90 Aluel Bol Deng F 76 Chuei-keer Manyang Keny

91 Abuol Chieng-kou F 69 Chuei-keer Manyang Keny

92 Ayen Akuei F 60 Chuei-keer Manyang Keny

93 Awuoi Alier F 56 Chuei-keer Garang Athiek

94 Akol Bol Angok M 70 Chuei-keer Marial Maluil

95 Achok But Kuot F 30 Chuei-keer Marial Maluil

96 Ameer Kuol Chol F 78 Chuei-keer Mach Kucha

97 Awal Kang Kon F 45 Chuei-keer Mach Kucha

98 Majok Akol Aguek M 55 Chuei-keer Aguto Chol

99 Kuol Yai Chol M 70 Chuei-keer Makuach Arem

100 Ngueny Kuany Deu M 80 Chuei-keer Makuach Arem

101 Joh Deng Makol M 45 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

102 Bol Arou Barach M 55 Kol-nyang Her-jok

103 Gai Manyang Ngong M 53 Kol-nyang Her-jok

104 Akuei Jok Magok M 52 Kol-nyang Her-jok

105 Riak Dot Nhial M 40 Kol-nyang Madit Aret

106 Aluong Alier Kur M 67 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

107 Ajak Mabil Ajak M 16 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

108 Wut-lok Gai Nhial F 65 Kol-nyang Madit Aret

109 Abeny Mach Ayool F 80 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

110 Aman Joh F 85 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

111 Maker Thuma Alier M 50 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

112 Aluel Alier Garang M 70 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

113 Panther Liok Deng M 95 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

114 Ayor Aguek Deng M 70 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

115 Akoi Garang Akoi M 65 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

116 Nyanchut Maleng Manyang F 40 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

117 Athiek Angeth Maper F 56 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

118 Ajah Maker Chuil F 40 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

119 Panther Mathiang Akau M 85 Kol-nyang Alier Alueng Gai

120 Bol Majok M 45 Kol-nyang Alier Alueng Gai

121 Mayom Dhol Alier M 80 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

122 Agot Kon Agot M 60 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

123 Arou Ajuong Kuol M 25 Kol-nyang Madit Aret Alier

124 Alier Deng Maluil Kuany M 40 Kol-nyang Madit Aret Alier

125 Mayen Liok Deng M 50 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

126 Kur Ngong Dot M 71 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

127 Marial Athou Malith M 35 Kol-nyang Madit Aret Alier

128 Deng Tit Deng M 30 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

129 Nyabol Anyang Bol F 40 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

130 Akuany Garang F 50 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

131 Mach Deng-koor Guut M 40 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

132 Ayen Yuen Lueth F 45 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

133 Athieng Aguto Nhial F 41 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

134 Gong Dot Gong M 45 Kol-nyang Madit Aret Alier

135 Chuti Ngueny Kuany F 35 Kol-nyang Madit Aret Alier

136 Ayiu Mach Ngong M 75 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

137 Panchol Athieu Bol M 80 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

138 Majok Nyiel Nhial M 75 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

139 Ajak Mach Pach M 85 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

140 Anyuon Malueth Aret M 40 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

141 Jok Akoi Alier-mapien M 35 Kol-nyang Madit Aret Alier

142 Ayor Anyieth Dut M 59 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

143 Kur Mony-roor Pach M 32 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

144 Alier Kuol Aman M 32 Kol-nyang Madit Aret Alier

145 Nyantuong Mading Riak F 35 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

146 Ayuen Malou Akol M 65 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

147 Makech Mach Bol M 50 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

148 Anyieth Deng Ayuen F 45 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

149 Achol Chuer-wei Anyieth F 45 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

150 Nyandit Riak Garang F 60 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

151 Mabior Koriom Leek M 70 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

152 Akuok Ajak Ajang F 50 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

153 Adol Aluong Aguek F 35 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

154 Achol Magot Adhuol F 45 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

155 Nyaroor Gon Nguon F 65 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

156 Gok Maduer Thiech F 50 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

157 Chier Achiek Madul M 60 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

158 Tholony Kuol Deng F 35 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

159 Amer Deng Athou F 50 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

160 Lony Angok Jok M 60 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

161 Athiek Reng Alier Bior F 45 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

162 Alier Achol Alier M 70 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

163 Jumbo Yuot Yom M 60 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

164 Akur-dit Madit Jongkuch F 6 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

165 Akim Madit Jongkuch M 4 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

166 Abiei Makech Mach F 10 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

167 Bol Makech Mach M 8 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

168 Anyieth Makech Mach F 6 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

169 Makuei Makech Mach M 4 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

170 Ruben Agau Bol Garang M 7 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

171 Awuoi Adhuma Pach F 7 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

172 Akuol Adhuma Pach F 7 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

173 Ajah Adhuma Pach F 4 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

174 Riak Simon Deng Yau M 2 Kol-nyang Mayom Malak

175 Mayom Arou Ngang M 32 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

176 Agumut Chok Deng M 55 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

177 Bolich Barach Ajak M 55 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

178 Achol Mabil Nuer F 67 Kol-nyang Guut Ajuong

179 Lual-jok Ajak Lual-jok M 45 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

180 Keth Anuol Chol F 45 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

181 Guet Jok Anyang m 44 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

182 Arem Pach Dit M 53 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

183 Jok Aguto Pach M 22 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

184 Angau Pach Dit M 78 Kol-nyang Nyok Alier

185 Majok Awel Alier Garang M 60 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

186 Panther Majok Nyiel Nhial M 25 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

187 Athou Bior Anyieth F 32 Kol-nyang Deng Bol

188 Wal Mayol Pach Ahok M 25 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

189 Chol Mayol Pach Ahok M 28 Kol-nyang Marial Alier

190 Chuti Ngueny Kuany-deu M 75 Kol-nyang Madit Aret Alier

191 Garang Diing Garang M 28 Kol-nyang Her-jok Garang

S/NO. NAME IN FULL SEX AGE BOMA REMARK

1 Piok Ajak Kur m 55 Pajhok Pakom

2 Amer Garang Atem f 35 Pajhok Pakom

3 Mayen Aluong Mayen m 64 Police Pakom

4 Ajith Nook Anyang m 68 Police Pakom

5 Anyang Ajith Nook m 18 Police Pakom

6 Nyanman Jok Abuoi f 62 Police Pakom

7 Mabat Aguto Jool m 69 Apierwuong

8 Mawut Nyok Ding m 55 Apierwuong

9 Adongwei Kuol Deng f 45 Police Pakom

10 Deng Majok Kur m 19 Apierwuong

11 Ayen Kuol Kuai f 21 Apierwuong

12 Mading Jok Mayen m 70 Police Pakom

13 Dit Deng Gong m 70 Pajhok Pakom

14 Nyanthiec Awar Dit f 62 Police Pakom

15 Aman Maker Guut f 62 Police Pakom

16 Aluel Riak Keer f 65 Police Pakom

17 Leek Deng Chol m 38 Pajhok Pakom

18 Achiek Lueth Kulang m 61 Apierwuong

19 Maler Gai Kuai m 38 Police Pakom

20 Mawut Ayen Kuol m 55 Police Pakom

21 Ayen Jok Yuang f 61 Police Pakom

22 Garang Ayom Mach m 66 Pajhok Pakom

23 Appolo Pach Gar m 76 Leekrieth

24 Majok Akhau Leek m 62 Leekrieth

25 Machol Ngong Agok m 72 Leekrieth

26 Amuor Agoot Madol f 81 Leekrieth

27 Ayuen Jok Madol m 65 Leekrieth

28 Madol Kom Bior m 58 Leekrieth

29 Mayola Anyieth Akhau m 69 Leekrieth

30 Yar Anyieth Akhau f 71 Leekrieth

31 Apieu Biar Leek m 80 Leekrieth

32 Nyankor Pach Lukuac m 60 Leekrieth

33 Goop Ateny Kuereng m 56 Leekrieth

34 Nyok Bior Nyok m 15 Leekrieth

35 Piel Mayen Deng m 62 Leekrieth

36 Chol Nyok Ayook m 76 Leekrieth

37 Alier Maror Anyang m 54 Leekrieth

38 Nyuon Achien Pach m 71 Leekrieth

39 Bior Deng Yong m 63 Leekrieth

40 Amuor Deng Kuot f 71 Leekrieth

41 Ngong Chol Ajith m 6 Leekrieth

42 Yar Chol Ajith f 4 Leekrieth

43 Agok Machar Mayen m 66 Leekrieth

44 Manyok Dut Akuang m 73 Leekrieth

45 Mangar Leek Buol m 31 Leekrieth

46 Agot Leek Ateer f 70 Chuei-Magoon Chot

47 Nyanwut Achol Kon m 65 Chuei-Magoon Chot

48 Achok Nyueny Dot m 45 Chuei-Magoon Chot

49 Nyalueth Thiong Anyuat m 61 Chuei-Magoon Chot

50 Aluel Borong Anaai m 72 Chuei-Magoon Chot

51 Ajah Buol Manyang m 45 Chuei-Magoon Chot

52 Yar Awuol Deng m 62 Chuei-Magoon Chot

53 Bol Machol Mayen m 35 Chuei-Magoon Chot

54 Ayen Achiek Nhial f 55 Chuei-Magoon Chot

55 Ayuen Reng Mayom m 75 Chuei-Magoon Chot

56 Riak Reng Mayom m 62 Chuei-Magoon Chot

57 Alier Makol Bior m 65 Keer

58 Deng Angui Deng m 65 Chot

59 Makol Agou Makur m 80 Keer

60 Aleek Biar Mach f 71 Keer

61 Aliet Deng Akol f 62 Keer

62 Garang Deng Gar m 80 Keer

63 Achuerwei Deng Bior f 92 Keer

64 Keny Dekbai Riak m 37 Keer

65 Athieng Garang Alith f 80 Keer

66 Tholhok Yuang Nyieth m 87 Keer

67 Tiit Mabior Dekbai f 3 Chuei-Magoon Chot

68 Ayuen Kuol Kur m 38 Chuei-Magoon Chot

69 Ayuiu Mach Ngong m 75 Chuei-Magoon Chot

70 Akuol Kelei Ayol f 68 Chuei-Magoon Chot

71 Abiar Deng m 76 Chuei-Magoon Chot

72 Amoth Wuoi Agot m 72 Chuei-Magoon Chot

73 Erjok Machar Achuoth m 37 Chuei-Magoon Chot

74 Madol Lueth Mayen m 80 Chuei-Magoon Chot

75 Diing Deng Pakam f 37 Chuei-Magoon Chot

76 Mayen Madol Lueth m 2 Chuei-Magoon Chot

77 Nyanluak Alueng Ajuoi f 61 Chuei-Magoon Chot

78 Ayak Athiek Kur f 74 Chuei-Magoon Chot

79 Akuac Akuot Achuil f 81 Chuei-Magoon Chot

80 Mach Magon Awal m 50 Chuei-Magoon Chot

81 Achol Mach Lual f 80 Chuei-Magoon Chot

82 Awuoi Gai Nai f 80 Chuei-Magoon Chot

83 Abiei Malual Ayom f 87 Chuei-Magoon Chot

84 Ajah Yom Doot f 102 Chuei-Magoon Chot

85 Mach Gar Mach m 81 Chuei-Magoon Chot

86 Gar Kuek Gar m 30 Chuei-Magoon Chot

87 Awan Kuol Lual m 41 Chuei-Magoon Chot

88 Yar Ajok Geu f 50 Chuei-Magoon Chot

89 Nyankoor Leek Deng f 50 Chuei-Magoon Chot

90 Nyalueth Deng Bol m 78 Chuei-Magoon Chot

91 Nyabol Mach Wel m 52 Chuei-Magoon Chot

92 Ayuen Akhau Wel m 37 Chuei-Magoon Chot

93 Mamer Garang Tuung m 31 Chuei-Magoon Chot

94 Abiok Garang Deng f 83 Chuei-Magoon Chot

95 Achol Achiek Thok f 5 Chuei-Magoon Chot

96 Ngong Achiek Thok m 2 Chuei-Magoon Chot

97 Agok Kuol Deng f 40 Chuei-Magoon Chot

98 Chol Akol Bol m 3 Chuei-Magoon Chot

99 Akuek Deng Garang f 80 Chuei-Magoon Chot

100 Maluak Kang Jang m 35 Chuei-Magoon Chot

101 Jombo Apeech Ngong f 77 Chuei-Magoon Chot

102 Atong Diing Thok m 3 Chuei-Magoon Chot

103 Matuur Akech Chaboc m 35 Chuei-Magoon Chot

104 Achol Mach Chiek f 66 Chuei-Magoon Chot

105 Chol Garang Kur m 31 Chuei-Magoon Chot

106 Keth Guet f 68 Chuei-Magoon Chot

107 Akon Majok Luil f 50 Chuei-Magoon Chot

108 Angau Mach Ngong m 76 Chuei-Magoon Chot

109 Aliet Jual Anyang f 61 Chuei-Magoon Chot

110 Deng Nyok Anyieth m 28 Chuei-Magoon Chot

111 Nyabol Jok Deng f 53 Chuei-Magoon Chot

112 Mach Mayen Mayen m 2 Chuei-Magoon Chot

113 Jok Malek Deng m 40 Chuei-Magoon Chot

114 Abuui Mawut Abui m 43 Chuei-Magoon Chot

115 Abui Pur Abui m 51 Chuei-Magoon Chot

116 Gai Kelei Gai m 51 Chuei-Magoon Chot

117 Kuol Kuei Kur m 67 Chuei-Magoon Chot

118 Yar Gai Akuei f 82 Chuei-Magoon Chot

119 Deng Gaak Goch m 61 Chuei-Magoon Chot

120 Ngor Ayor Abui m 28 Chuei-Magoon Chot

121 Geu Yar Jok m 30 Chuei-Magoon Chot

122 Ayuen Achuei Gureech m 28 Chuei-Magoon Chot

123 Aguorjok Achiek Duot f 90 Chuei-Magoon Chot

124 Ding Ajith Nyok m 28 Mareng Apierweng

125 Mach Bol Ding m 60 Mareng Apierweng

126 Nyanchol Yuot Piel f 45 Mareng Apierweng

127 Akuut Pach Nai m 50 Mareng Apierweng

128 Akeer Riak Achien m 61 Mareng Apierweng

129 Aluel Leek Atuongjok m 45 Mareng Apierweng

130 Mach Lueth Mach m 50 Mareng Apierweng

131 Kuol Mathiang Deng m 51 Chuei-Magoon Chot

132 Mamer Garang Ayol m 35 Chuei-Magoon Chot

133 Mabiei Mayom Abuk m 32 Mareng Apierweng

134 Akech Makuei Ding m 35 Thianwei Boma

135 Bheer Kuol Anyieth m 40 Thianwei Boma

136 Agau Makol Ayath m 32 Thianwei Boma

137 Mach Madol Deng m 40 Thianwei Boma

138 Alier Ayuel Chengkou m 70 Thianwei Boma

139 Kelei Deng Ding m 80 Thianwei Boma

140 Kuec Tuung Lual m 70 Thianwei Boma

141 Kuei Nhial Lual m 90 Thianwei Boma

142 Achol Tong Kur m 82 Thianwei Boma

143 Akol Lukuac Bior f 90 Thianwei Boma

144 Ayong Deng Achuk f 87 Thianwei Boma

145 Yar Thiong Ayuel m 81 Thianwei Boma

146 Abuoi Jool Garang m 50 Thianwei Boma

147 Athieng Aguto Chol m 106 Thianwei Boma

148 Ajok Anyieth Achuoth m 56 Thianwei Boma

149 Abuol Garang Chol f 83 Thianwei Boma

150 Mayom Ngong Deng m 79 Thianwei Boma

151 Koor Jok Lieth f 86 Thianwei Boma

152 Athiek Anyier Akok m 79 Thianwei Boma

153 Chuti Yuol Aguto m 69 Thianwei Boma

154 Akueth Jok Ding m 80 Thianwei Boma

155 Adum Magaar f 71 Thianwei Boma

156 Ding Mangok Chol f 68 Thianwei Boma

157 Ngong Majok Ngong m 50 Thianwei Boma

158 Aluet Deng Garang f 95 Thianwei Boma

159 Maluk Mach Ding m 70 Thianwei Boma

160 Ajuong Ding Majuc m 34 Mareng Apierweng

161 Ayom Mayen Deng m 29 Mareng Apierweng

162 Ayuen Magot Bol m 46 Chuei-Magoon Chot

163 Lual Magot Bol m 38 Chuei-Magoon Chot

164 Achol Mach Achol m 60 Chuei-Magoon Chot

165 Lako Bol Mach m 38 Mareng Kucdok

166 Thon Mach Maluk m 41 Mareng Kucdok

167 Mabiel Kuei Mach m 50 Mareng Kucdok

168 Garang Mading Eguei m 30 Mareng Kucdok

169 Thon MalukMach m 30 Mareng Kucdok

170 Kuei Juac Kuonjok f 50 Mareng Kucdok

171 Guguei Majier Kuei m 26 Mareng Kucdok

172 Ayen Manyang Mach f 2 Mareng Kucdok

173 Garang Chuang Thiong m 50 Mareng Kucdok

174 Yom Ateng Dhelic f 60 Mareng Kucdok

175 Ding Lual m 90 Mareng Kucdok

176 Mach Long Mach m 90 Mareng Kucdok

177 Jambo Guec Mach f 50 Mareng Kucdok

178 Bior Arou f 88 Mareng Kucdok

179 Ateng Dhelic m 41 Mareng Kucdok

180 Makoi Wel Magot m 5 Mareng Kucdok

181 Ayen Mangar Ayuen f 40 Mareng Kucdok

182 Ayak Majok Geu f 2 Apierwuong

183 Ayoom Adiir Ayoom m 82 Chuei-Magoon Chot

184 Philip Achol Mach Achol m 50 Chuei-Magoon Chot

185 Mamer Garang Ayool m 30 Chuei-Magoon Chot

186 Mabiei Akol Deng m 40 Thianwei Boma

187 Thon Jok Nyuop m 30 Thianwei Boma

188 Mayen Amoth Nyuop m 28 Thianwei Boma

SUBJECT: BEING LIST OF PEOPLE WHO WERE KILLED BY RIAK MACHAR’S REBEL GROUP IN MAKUACH PAYAM FROM 18TH/DEC/2014 UPTO 19TH/JANUARY 2014 IN BOR COUNTY – JONGLEI STATE – BOR.

S/No Name in Full Sex Age Boma Payam

- Majok Agok Ayaat M 52 yrs werkook makuac

- Mathiang Guet Chuit M 60 yrs werkook makuac

- Kuol Garang Leek M 35 yrs werkook makuac

- Lueth Garang Leeth M 45 yrs werkook makuac

- Awut Kuol Koryom M 50 yrs werkook makuac

- Diing Arou Jur F 62 yrs werkook makuac

- Hoka Aguek Hoka M 46 yrs werkook makuac

- Garang Makuac Mathiang M 66 yrs werkook makuac

- Achol Nyakarah Tong M 42 yrs werkook makuac

- Dhaal Jok Mayen M 50 yrs werkook makuac

- Athel Khou Nhial M 48 yrs werkook makuac

- Madit Mac Jok M 62 yrs werkook makuac

- Deng Makuac Anyang M 59 yrs werkook makuac

- Abuk Chak Bior F 52 yrs werkook makuac

- Ateny Bior Makol M 47 yrs werkook makuac

- Mawut Dhuong Nhial M 52yrs werkook makuac

- Madol Deng Ayom M 60yrs werkook makuac

- Mayol Marok Nhiany M 48yrs werkook makuac

- Kuol Ngong Aleeng M 52trs werkook makuac

- Deng Kuol Deng M 39yrs werkook makuac

- Bior Aguek Joh M 56yrs werkook makuac

- Panchol Ariik Deng M 72yrs werkook makuac

- Chol Deng Chol M 66yrs werkook makuac

- Mabior Ngang Akon M 62yrs werkook makuac

- Panchol Jakdit Bior M 58yrs werkook makuac

- Makuol Arok Dau M 52yrs werkook makuac

- Atem Aruu Atem M 48yrs werkook makuac

- Ajith Thon Deng M 46yrs werkook makuac

- Ayong Garang Deng M 52yrs werkook makuac

- Abuol Garang Mac M 60yrs werkook makuac

- Nyang Akol Nhial F 52yrs werkook makuac

- Ajoh Garang Adhuong F 48yrs werkook makuac

- Athou Jok Thok F 50yrs werkook makuac

- Nyalueth Jok Ajak F 46yrs werkook makuac

- Ayor Gor Moun F 60yrs werkook makuac

- Abuot Ayen Anyang M 43yrs werkook makuac

- Atony Japur F 39yrs werkook makuac

- Mayak Bior Thiek M 50yrs werkook makuac

- Maluk Reng Ayak M 65yrs werkook makuac

- Wuoi Jok Koryom M 68yrs werkook makuac

- Chier Jool Aduot M 55yrs werkook makuac

- Akim Guet Kuol F 50yrs werkook makuac

- Bior Ngong Anyang F 72yrs werkook makuac

- Yar Gai Duot F 49yrs werkook makuac

- Adau Kuol M 45yrs werkook makuac

- Manyok Anyang Chol F 60yrs werkook makuac

- Akuol Lual Dau M 52yrs werkook makuac

- Anyang Jok Ayom M 60yrs werkook makuac

- Gut Hoka Mathiang F 58yrs werkook makuac

- Barach Deng Barach M 50yrs werkook makuac

- Abuk Manyiel Chiman M 49yrs werkook makuac

- Ajah Reng Angeth M 53yrs Mading makuac

- Amach Niop Agok M 60yrs Mading makuac

- Agol Majuch Agol M 30yrs Mading makuac

- Nyandit Ajuot Ngang F 50yrs Mading makuac

- Angau Kamot Tong M 60yrs Mading makuac

- Machiek Majuch Nyok F 70yrs Mading makuac

- Anok Achirin Marrial M 80yrs Mading makuac

- Adol Agol Majuch F 36yrs Mading makuac

- Panchol Malou Lueth M 70yrs Mading makuac

- Abiar Tong Ajak M 90yrs Mading makuac

- Lual Pach Anguet M 40yrs Mading makuac

- Athiek Deng Marial F 50yrs Mading makuac

- Machok Deng Marial M 50yrs Mading makuac

- Non Angeth Mac M 60yrs Mading makuac

- Makur Riak Agol M 70yrs Mading makuac

- Deng Ayor Athiek F 18yrs Mading makuac

- Buya Ngong Anyang F 50yrs Mading makuac

- Apiu Ajak Anyang M 60yrs Mading makuac

- Abathou Kur Jok M 80yrs Mading makuac

- Ateny Nyanchok Majuch m 80yrs Mading makuac

- Machar Anyieth Agau M 60yrs Mading makuac

- Anyieth Yar Anyieth F 46yrs Mading makuac

- Bol Akol Yom F 65yrs Mading makuac

- Adhieu Nyieth Adhieu M 68yrs Mading makuac

- Akuol Ngong Jil F 70yrs Mading makuac

- Nyanthich Ngor Ngang M 18yrs Mading makuac

- Akuany Achol Awan F 80yrs Mading makuac

- Riak Achol Awan M 36yrs Mading makuac

- Panchol Agol Majuch M 40yrs Mading makuac

- Ngang Atem Mabior F 37yrs Mading makuac

- Athiek Akau Mel M 50yrs Mading makuac

- Choor Angeth Chaboch M 80yrs Mading makuac

- Kuol Nyieth Angeth M 60yrs Mading makuac

- Kuol Achiek Majuch M 70yrs Mading makuac

- Chiek Thiek Agol M 63yrs Mading makuac

- Nyanduck Makuac Aguek M 54yrs Mading makuac

- Aman Duop Jok M 60yrs Mading makuac

- Kuol Kudum Kur M 55yrs makuac makuac

- Amer Biar Wel F 49yrs makuac makuac

- Anger Riak Deng M 81yrs makuac makuac

- Athou Amuor Khok F 90yrs makuac makuac

- Agok Mabior Geu F 60yrs makuac makuac

- Yar Deng Kuot F 97yrs makuac makuac

- Aruar Piok Deng F 68yrs makuac makuac

- Agot Deng Dhieu F 72yrs makuac makuac

- Wal Kureng Akol M 80yrs makuac makuac

- Akut Mayen Yar F 69yrs makuac makuac

- Gai Machok Mading M 62yrs makuac makuac

- Ateny Piok Thon M 57yrs makuac makuac

- Yar Alier F 80yrs makuac makuac

- Anyieth Guet Piok F 60yrs makuac makuac

- Nyanlueth Ajok Lual F 82yrs makuac makuac

- Anyijong Kucha Leek F 73yrs makuac makuac

- Achiek Awuon Deng M 30yrs makuac makuac

- Deng Awuol Kur M 57yrs makuac makuac

- Kon Gai Ajok M 55yrs makuac makuac

- Achiek Deng Biar M 35yrs makuac makuac

- Achok Deng Anyang M 82yrs makuac makuac

- Athiei Kuol Aluk M 10yrs makuac makuac

- Achiek Deng Biar M 35yrs makuac makuac

- Achok Akuok Bior F 75yrs makuac makuac

- Nyiel Kud Aluk F 35yrs makuac makuac

- Achiek Monyror Yuot M 65yrs makuac makuac

- Bol Madol Kur F 43yrs makuac makuac

- Nhial Jool Malual M 13yrs makuac makuac

- Nyanyoum Deng Achuol F 86yrs makuac makuac

- Adier Nhial Gak M 96yrs makuac makuac

- Ajueil Garang Geu F 83yrs makuac makuac

- Majok Joh Anyieth F 55yrs makuac makuac

- Agot Majuch Biar F 82yrs makuac makuac

- Ajah Alier Aman F 55yrs makuac makuac

- Manyang Kuol Nyok M 30yrs makuac makuac

- Akoi Kuol Agau M 38yrs makuac makuac

- Mayol Ajak Chol M 48yrs makuac makuac

- Adol Makum Chienkou M 29yrs makuac makuac

- Achiek Deng Anyang M 52yrs makuac makuac

- Apech Riak Gai M 60yrs makuac makuac

- Chol Anyieth Kur M 46yrs makuac makuac

- Anyang Jok Anyang M 52yrs makuac makuac

- Amour Deng Anyang M 50yrs makuac makuac

- Ateny Nek Rech M 62yrs makuac makuac

- Mac Wai Mac F 58yrs makuac makuac

- Mac Leet Luala M 42yrs makuac makuac

- Guet Ajuoi Nai M 46yrs makuac makuac

- Ayak Bolek Poch M 55yrs makuac makuac

- Maluk Mach Bior F 50yrs makuac makuac

- Maguet Anyieth Akol F 58yrs makuac makuac

- Deng Riak Ajak M 72yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Agot Malual Jok M 80yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Mayen Duopo Riak M 61yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Abuol Makuac Akur M 55yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Aluel Ayuel Nyinger F 39yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Bol Akau M 45yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Ayen Kuot Ngong F 92yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Abuol Kuol Kur M 55yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Chol Kur Chol M 42yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Wel Jool Aker M 50yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Panchol Bheer Lual M 65yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Ajak Leek Ajak M 66yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Alier Mabior Bath M 32yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Deng Apar Ngang M 52yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Amuor Khok Chol F 48yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Mac Angau Nyok M 28yrs makuac makuac

- Bol Jok Ngong F 75yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Anyieth Lual Abuor F 80yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Ayen Kur Leet F 60yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Akur Kon Buut F 08yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Ayor Kona Ajak F 41yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Jool Wel Alier M 85yrs K/luaidit makuac

- Panchol Wel Alier M 45yrs K/luaidit makuac