(Reuters) – In December, the people of this town watched the national army stand by while thousands of young men from a rival ethnic group stormed in for a cattle raid. The interlopers shot and macheted hundreds of people, burned homes and stole tens of thousands of cows. One month on, the state minister for law enforcement arrived in this part of eastern South Sudan to convince residents that the fledgling nation’s new government was ready to help – and that they should give up their weapons. Gabriel Duop, a man built like a refrigerator, sat behind a wooden desk in a dirt field, a notebook in front of him. “We are the government,” he told the crowd. “And we want peace.” But the people wanted answers. Who, they asked, would protect them when the raiders returned? That the citizens of the world’s newest nation are making such demands is both a sign of progress and an indication of how far South Sudan has to go. Cattle raids are centuries old in the region. The expectation that a central government can and should halt them is much newer.

http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/07/09/us-south-sudan-governed-idUSBRE86806Q20120709

Special Report: For the world’s newest nation, a rocky start

Mon Jul 9, 2012 9:50am EDT

(This is the first in a series of articles: “Birthing a Nation – South Sudan’s first year.”)

By Alexander Dziadosz

(Reuters) – In December, the people of this town watched the national army stand by while thousands of young men from a rival ethnic group stormed in for a cattle raid. The interlopers shot and macheted hundreds of people, burned homes and stole tens of thousands of cows.

One month on, the state minister for law enforcement arrived in this part of eastern South Sudan to convince residents that the fledgling nation’s new government was ready to help – and that they should give up their weapons.

Gabriel Duop, a man built like a refrigerator, sat behind a wooden desk in a dirt field, a notebook in front of him.

“We are the government,” he told the crowd. “And we want peace.”

But the people wanted answers. Who, they asked, would protect them when the raiders returned?

That the citizens of the world’s newest nation are making such demands is both a sign of progress and an indication of how far South Sudan has to go. Cattle raids are centuries old in the region. The expectation that a central government can and should halt them is much newer.

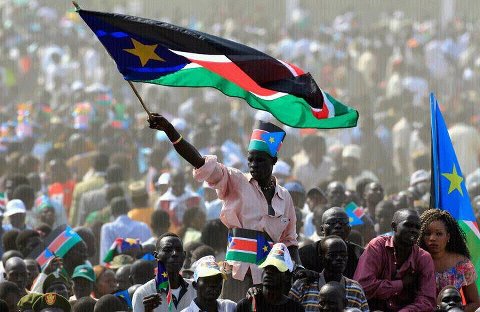

For decades, Sudan’s southerners fought the country’s predominately Arab rulers in the north. More than 2 million people died before the fighting ended in a peace deal in 2005. In a referendum promised by the pact, 99 percent of southerners chose to secede. And on July 9, 2011, the flag of South Sudan was raised over Juba, the rickety new capital.

In a series of articles, Reuters is chronicling the first year in the life of South Sudan – and assessing the odds of whether it will flourish or fail.

This country of about 8 million people has several things going for it – fertile soil, rich petroleum reserves and backing from the United States and other wealthy international donors.

But in many ways, South Sudan’s creation was a wild act of optimism. The landlocked country is embroiled in an often violent dispute with its old rulers in Sudan. Just one in four people are literate. Running water and hospital beds are scarce. And in a nation the size of France, there are only about 300 km (190 miles) of tarmac roads.

In short, there’s every possibility South Sudan could join the ranks of the world’s failed states, adding to instability in a part of the world already dogged by separatist rebellions, Islamist militants, corruption and poverty.

The first year of independence has brought hope and pride, but also graft and missteps – not least an economically disastrous dispute with Sudan over oil that has threatened to turn into a new war. The row has led Juba to shut down its oil industry, which provided an astonishing 98 percent of state income. Domestic crises like the murderous cattle raid in Pibor have tested the government’s ability to provide the most fundamental of services, security.

The first year has also brought questions about what it means to be a citizen of South Sudan. This is especially true in states such as Jonglei, where Pibor lies. There, smaller tribes have long had a tense relationship with the country’s two biggest, the Dinka and the Nuer, which dominate the government.

Most of Pibor’s residents are Murle (pronounced “mur-lay”), numbering an estimated 150,000 people.

In interviews with dozens of Murle leaders and citizens, most remained hopeful their new government would bring development and security. But many were frustrated about broken promises and increasingly worried they might have traded one set of remote and neglectful rulers for another. Crucially, the government has so far failed to convince every South Sudanese that they belong.

“We don’t have roads, we don’t have hospitals,” said Peter Gazulu, a Murle who is close to some of the group’s most influential leaders. “Why are we denied representation? Why are we denied development? … We fought 21 years for democracy and freedom for all, so why has it become a democracy for the few?”

Officials in the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement, the ruling party, dismiss charges of neglect and say frictions among the nation’s ethnic groups are rooted in years of misrule by the Sudanese government in Khartoum. With time and control of its resources, South Sudan can overcome this.

The post-raid meeting in Pibor suggests that won’t be easy.

So deep was the lack of trust in the central government, one woman said she had almost been too scared to show up. She suggested Vice President Riek Machar, a Nuer, had played a role in the raids – a claim few outside the town take seriously.

Machar had addressed a meeting in Pibor in December and assured people the town would be safe, the woman said. But the raiders stormed in just days later.

“The vice president arrived here, and those people came right away,” she said, drawing applause from the crowd that hugged the shade of a neem tree.

Machar’s office did not respond to requests for an interview, but he and other officials have said he went to Pibor to try to persuade the attackers to go home. The heavily armed young men refused.

When people had finished airing their grievances, Duop, the state law minister, stood to speak. The sun poured down on him and the crowd.

Officials were working with aid agencies, talking to the media, doing everything they could to help, he said. The government planned to deploy troops between the Nuer and Murle to prevent more raids, and would even consider a Murle request to split the region off into its own state.

Rumors that Machar had assisted his fellow Nuer in the raid were nonsense, Duop said. “Riek Machar loves his people … Now we have our own nation, and we don’t want our people to die.”

Duop said he would take the same message to a large Nuer town.

At the end of the minister’s speech, people clapped politely and a couple of men approached to shake his hand.

“Good meeting,” Duop said, and smiled as people filed out.

When the field had mostly emptied, Samuel Chachin, a tall, balding pastor with a thin moustache, approached a reporter.

The people did not believe the state minister, he said.

THE IMPORTANCE OF COWS

Pibor is poor even for South Sudan.

In the dry season, the sun bakes the dirt roads so hard they feel like pavement. In the wet season, rain turns the ground to mud. The air buzzes with insects. Place an apple core on the ground and within a minute it will turn black with flies and ants.

Children in stained, tattered rags fashion toy pickup trucks out of rusted vegetable oil tins stamped “USAID,” the acronym of the U.S. government aid agency. Most of the real pickups belong to aid groups, the United Nations or the national army.

All but a few people live in one-room, stick-and-mud huts.

“People still have that life of a long time ago,” said David Adoch, a stocky man working as an administrator at the Pibor county government headquarters who put his age around 36.

Most people grow their own food and get by without needing much money. A well-paid government worker or trader – about the only people who use cash – might expect to make 700 South Sudanese pounds a month, or around $140 at recent black market rates. Sorghum, a staple food, now costs over five pounds ($1) a kilo in parts of Jonglei state.

Part of the area’s poverty owes to its isolation. Trucking in basic materials like cement and iron sheeting is costly. It is a common problem in South Sudan, and one reason the state has virtually no presence outside the three or four main centers.

Foreign aid agencies provide almost all the basic services in Pibor, including water and health services. “If we’re not there, there is simply no health care,” Karel Janssens, a field coordinator for Doctors Without Borders, said of a Murle village near Pibor.

The harsh terrain and remoteness are not the only cause of the area’s sense of isolation and neglect. During the civil war, many Murle sided with Khartoum against the southern rebels, who were led and dominated by the Dinka. That rivalry with the bigger groups, as well as a history of back-and-forth cattle raiding, has left a legacy of animosity and prejudice.

Cows are everything in South Sudan. For Murle and other tribes, cattle are part of nearly every social structure and basic desire: wealth, marriage, status, influence.

A Murle man’s family is expected to pay a dowry of cattle to his bride’s family. Cow milk mixed with cow blood is a prized drink. If a Murle commits murder, he compensates the victim’s family in cows.

“If you have just 10 cows, people will not consider you. You’re like a spoon – only for eating and throwing down. You cannot eat also. You’re for using,” said Joseph, a local government worker, with a laugh. “If you have many cows, people will respect you. They’ll greet you in a respectful way.”

Raids and counter-raids have cycled for centuries, gradually becoming bloodier as guns and satellite phones flooded in and young men became less responsive to local elders’ pleas for them to stop. With no real chance for people to appeal to the law when rivals steal their cows, the incentive to steal back is high.

THE “WHITE ARMY”

In the December raid, an estimated 6,000 to 8,000 young men from the Lou-Nuer – a sub-group of the Nuer – marched on Murle territory. They called themselves the “White Army,” a name first taken by another Nuer group during the civil war whose fighters smeared white ash on their torsos to guard against insects.

On December 23, as pastor Chachin and church members in his hometown of Lekwanglei practised songs and prepared food for Christmas, Murle started to arrive from the north. They were injured and had stories of carnage.

“The people were running. They said, ‘The Nuer are coming now,'” Chachin recalled. His family and other villagers walked through the night the 40 km (25 miles) or so to Pibor. There, he and his wife, Rebecca, and their five children moved into a small hut near the main church. By December 31, raiders had arrived at the town’s outskirts. The family fled again.

“You could see the smoke. They were burning the houses,” Chachin said of the raid on Pibor.

The Doctors Without Borders clinic and dozens of homes were ransacked. Pastor Chachin said raiders shot his mother as she fled across a river, killing her.

Another man, Lela Agolo, said his wife and children were shot dead while sleeping in the grass after fleeing their village.

The attackers began withdrawing on January 3. “They were able to do so unchallenged and have continued to enjoy impunity,” the human rights division of the U.N. Mission in South Sudan reported last month.

The scale of the damage was dramatic. Lekwanglei was reduced to little more than a field of cow bones, crushed jerry cans, and the blackened remains of huts. The village school, one of few concrete structures, was smashed and burned, its walls covered in graffiti. “We are not going to leave,” one slogan read.

Kurkur Golla, who put her age at around 60, said she had witnessed cattle raids since her youth. Back then, she said, “The young people were not like these. They only came and took cattle. They didn’t kill children and old people.”

Mediators stress that the conflict is far from one-sided. The rampage was the latest in a series of tit-for-tat attacks that many say was triggered by a 2009 Murle raid on the Lou-Nuer.

“Lou-Nuer do go and raid, and Murle do go and raid,” said Gatwech Koak Nyuon, a member of the Nuer Peace Council, a local group that has tried to end the violence.

The death toll is disputed. Pibor’s commissioner, Joshua Konyi, put the figure at 3,141. The U.N. human rights report said there were 612 confirmed deaths in the attacks on Murle settlements, although more deaths had been reported. Another 276 people died in revenge attacks on Lou-Nuer and Dinka communities, it said.

Murle were particularly bitter that neither South Sudan’s army, which is stationed in both Lekwanglei and Pibor, nor the local contingent of U.N. peacekeepers, were able to halt the onslaught.

Several survivors claimed Nuer members of the national army had joined in the raids.

Peter Kaka, a 32-year-old Murle soldier in the army, was stationed in Pibor and there during the raid. He said he and the other troops had been given orders to hold back and not intervene, but he did not know why.

“It was a surprise to the (Pibor) community,” he said. “When we were brought from Juba, we were told by our commanders that we were going to deploy in different areas so that we would defend them from external attack. We did nothing. We were just like a throat which is not swallowing the food.”

The Sudan People’s Liberation Army, as South Sudan’s national army is called, says its 400 to 600 soldiers did not intervene because they were outnumbered by the well-armed and organized attackers. A lack of roads and transport made it impossible, despite U.N. warnings, to mobilize enough troops to protect civilians.

Army spokesman Philip Aguer said any order to confront the raiders head-on would have been a “suicidal act.” Aguer said 11 soldiers were reported to have deserted amid the attacks. “Whether they joined the fighters, we are not sure,” he said. The government has since sent thousands of soldiers to Jonglei to prevent further attacks.

The U.N. mission says it did everything it could and that its presence stopped raiders from attacking people inside the center of Pibor.

“The combined use of deterrence, early warning and show of force did protect civilians,” the mission’s spokesman said in an emailed comment. The primary responsibility for protecting the country’s civilians, he added, “remains with its young government.”

A “NEW SUDAN”

During colonial rule, British administrators tried to keep the south and its patchwork of tribes separate from the largely Arabic north. When London granted independence in 1956, it left an Arab government in Khartoum, which reneged on a promise of a federal state. War between north and south battered the country until a peace agreement in 1972.

In 1983, John Garang, a charismatic southerner in the Sudanese national army, led a mutiny that reignited the conflict. With other commanders, Garang, a Dinka, built the rebel army into a force to take on Khartoum.

Garang imagined a “New Sudan” that would embrace democracy and give every ethnic and religious group equal sway. Unlike many of his fellow rebels, he opposed secession and wanted to remake the country as a unified whole.

Two decades of fighting followed until a peace deal was signed in 2005. Soon after, Garang died in a helicopter crash. His deputy, Salva Kiir, who had been keener on secession, took over.

Garang’s photo still hangs on the walls of offices and government buildings in Juba, but with secession, his vision of a multi-ethnic, unified Sudan died.

Kiir, now president, says he is committed to building an inclusive state in South Sudan. But for people like Akot Maze, the 47-year-old former commissioner of Pibor county, it’s not the same.

Maze was in secondary school when the civil war restarted. Like thousands of other students, he was caught up in the revolutionary fervor. A stint in the nascent Sudan People’s Liberation Army transformed how he thought about identity and tribe.

“Eventually, every student from Bor, from Equatoria, from Malakal, from Khartoum, we just met in the bush,” he said. The aim was to make a nation in which people “don’t know what tribe they belong to, but know what country they belong to.”

Two years into the peace deal, Maze was appointed commissioner of Pibor county. He expected peace would bring development and link the region to the rest of the south.

But in the six years between the peace deal and independence last year, his hopes have faded.

Officials from South Sudan’s government-in-waiting promised new projects, but rarely delivered. When Kiir visited Pibor in 2007, he promised two primary schools, a secondary school and a hospital, to be named after a prominent Murle commander, Maze said. None of it has been built. A plaque to mark the site of the hospital is crumbling, the name of the would-be building erased by the sun and rain.

Maze’s frustration led to a dispute with Jonglei state governor Kuol Manyang, one of the army’s most powerful commanders. The governor sacked Maze last year. Maze said he had accused the state of discrimination against the Murle, and suspected he was being punished for speaking up.

Manyang said the two did not have a good working relationship and that Maze had not been cooperating. “It’s not the first time for a person to be shuffled,” Manyang said.

Maze left his post in December, just days before the Nuer raiders reached Pibor.

A FAMILIAR PATTERN

Several hours after state security minister Duop spoke to Pibor residents about the cattle raid, he sat down with Joshua Konyi, the commissioner who replaced Maze. The two old soldiers had fought side-by-side in a 1987 battle in which the SPLA captured Pibor from the pro-north, largely Murle militia that controlled the area for most of the war. Now they sat outside in the fading light, sipping tea from plastic cups.

“The first place where I shot a bullet was here, in Pibor,” said Duop, who put his age at around 14 at the time. Duop talked about his friendship with Konyi, a Murle, and how the camaraderie of the war years was evidence that divisions between South Sudan’s diverse people could be overcome.

But in other ways he seemed dismissive of the country’s smaller ethnic groups.

“I know why we fought the war. We fought to liberate these people,” he said. “We are not in a position to let them kill themselves because of ignorance and poverty.”

Murle leaders agree a lack of economic opportunity is the main reason for the violence, but say Duop and the government miss an important point: For all its talk about peace and security and development, the government seems unable to deliver the most basic services.

Instead, they say, authorities rely on short-sighted and unworkable disarmament campaigns managed by the army, a sprawling organization made up of former militias.

After the raids, Murle leaders requested a peace conference with the Lou-Nuer to try to avoid any more attacks. But before that happened, the government had begun collecting guns from locals, including policemen. To many, it was a familiar pattern.

“They have no long-term plan,” Maze said of the government’s reaction.

Without more progress, some Murle may start to turn against the ruling party, he said. “We try to convince them that the government is a government of all, not a government of Dinka or Nuer. But that feeling is there.”

The sense of alienation has left people like pastor Chachin worried about the future. By April, he was planning how he might send his children away, to escape the violence and poverty. Yei, a town in the south near the border with Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda, sounded promising, he said.

Maze had begun considering ways he might rejoin the national army, and was less pessimistic. But he did not expect much from the government.

“Now to talk about opening roads to the area, to talk about opening a school, to talk about opening a clinic, hospital and all that – I think it is a dream,” he said.

(Edited by Simon Robinson and Michael Williams)

http://www.reuters.com/article/2012/07/09/us-south-sudan-governed-idUSBRE86806Q20120709